- The Mexican economy is already likely growing above potential and the 2024 budget adds fuel to a hot burning fire. Concerns over public sector stimulus and sticky core inflation are the main issues keeping Banxico’s board more hawkish than some regional peers.

- The main driver of domestic growth in 2024 will be public and private consumption, particularly by lower income households. The 2024 Public Sector Economic Package foresees a material boost in public spending directed at consumption, coming on top of strong remittances at around 1% of GDP.

- Investment trends are mixed. The recent spike in construction spending is strongly linked to the government’s core infrastructure projects, and the rise in machinery and equipment investment is centered in purchases of foreign transportation equipment.

- Mexico’s next president, to be chosen in June 2024, will face a challenging deficit reduction task and turning around the country’s shortfalls in energy production and transmission that may be limiting the manufacturing sector’s expansion—and impacting Mexico’s nearshoring appeal.

As the IMF wrote in its recent Article IV consultation, the Mexican economy is already likely growing above potential and the 2024 budget adds fuel to a hot burning fire. Banxico’s latest Quarterly Inflation Report placed the output gap in “above potential” territory, and sees it staying there until at least late in 2025. Hence, we anticipate the board will keep monetary conditions tight for the foreseeable future, although there are scenarios under which we could see a gradual reduction of the tight settings.

We believe concerns over public sector stimulus alongside sticky core inflation are the main issues keeping Banxico’s board more hawkish/cautious than some regional peers (we expect the first cut will be in March 2024, see table 1). The forecasts outlined in table 1 have important sources of uncertainty around them, including:

- We believe Banxico will likely watch real policy rates over core inflation, and if the public spending acceleration pushes core CPI higher (a non-negligible risk), then rate cuts could be pushed out. On the flip side, easing core inflation could allow for gradual easing (our base case).

- We also anticipate that Banxico will monitor its policy rate differential to the FOMC, and although some cushion has been built (575bps, currently), we don’t expect Banxico will reduce its policy rate spread over the Fed to less than 450bps. We expect Mexico’s “terminal rate” to be around 6.50-7.00%, but we expect that level to arrive one to two years from now (with the timing dependent on both external and domestic factors).

- On economic activity, although we have a higher than consensus forecast for 2024, we believe GDP growth will be highly front loaded, and highly focused on consumption spending. We expect a strong post-election slump in domestic demand.

- We anticipate that the looming June 2024 elections and uncertainty over some key policy areas will keep private investment relatively in check, particularly until we have more clarity on the power sector plans of the main candidates (see below).

CONSUMPTION TO DRIVE ECONOMY WITH HELP OF GROWING DEFICIT

On the public sector front, the 2024 Public Sector Economic Package foresees a material boost in public spending that will take the Public Sector Borrowing Requirements—the PSBR, a broad definition of the public deficit—up from 3.9% of GDP to 5.4% of GDP, while physical investment is falling (from 2.8% of GDP to 2.6% of GDP). This means that the bulk of the increase in public spending is likely to be directed at consumption (programmed & social spending). This support to consumption comes on top of around a full percentage point of GDP in “imported stimulus”, i.e., that which has come from strong remittances; remittances are currently running around USD10–15bn above the pre-pandemic trend, towards a pace of USD65bn per year, or close to 1% of GDP. These two factors taken together suggests that the strongest driver of domestic growth will be public and private consumption, particularly by lower income households.

The budget package estimates that, after a widening of the deficit in 2024, the PSBR will fall to 2.6% of GDP in 2025. However, most of the spending increase is coming from programmed spending and social transfers, and recall that AMLO protected his core social programs at the Constitutional level, which means such a deficit reduction will be a challenge for whatever administration takes over in 2024.

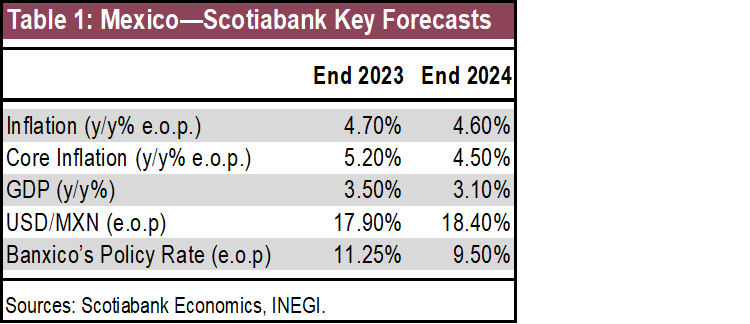

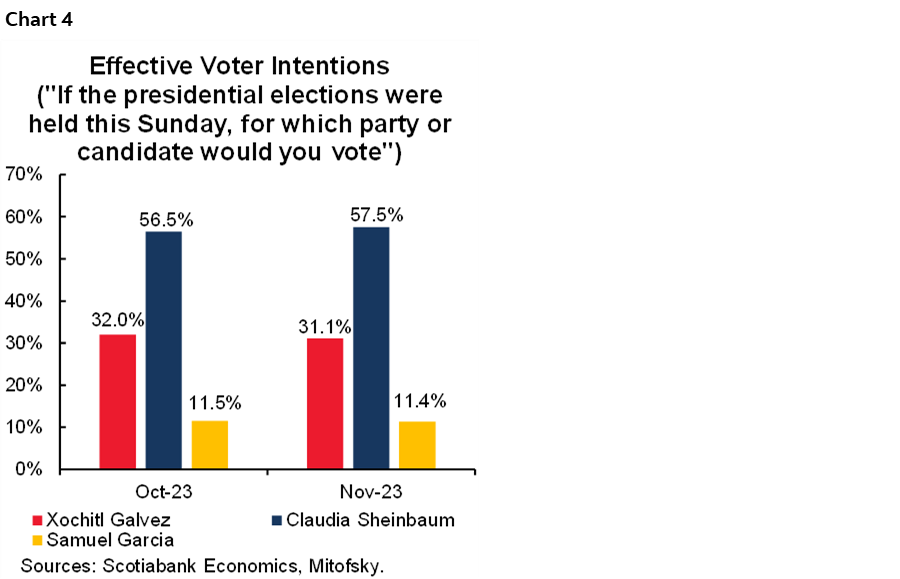

INVESTMENT SPENDING SURGE IS NARROWLY-FOCUSED

On the investment front, the news remains mixed. We have seen a recent spike in investment spending, but it remains concentrated in certain sub-components. On the construction front, the recovery has been concentrated in non-residential construction, which is strongly linked to efforts to finish the government’s core infrastructure projects. Data on this front have been somewhat questioned, in part because the spike in the output of construction sectors to the government’s projects (being coordinated and built by the army) don’t seem to match data for “hours worked” (see charts 1–3). In addition, public investment as a share of GDP has been quite flat, hovering just under 3.0% of GDP.

As for machinery and equipment investment, the subcomponents which are rebounding strongly are primarily imported transportation equipment, rather than domestically-produced, which results in a subtraction from GDP (imports are a negative in GDP accounting). Part of the recovery in transportation equipment investment is likely due to a replenishment of depreciated equipment following 4–5 years of abnormally low investment in these sectors; out of the different components of investment this equipment has among the fastest depreciation schedules.

LOOK AHEAD TO MEXICO’S 2024 ELECTIONS AND PROCESS

Mexico’s 2024 Electoral race is more formally kicking off, following the start of the pre-campaign process on November 20th. The elections will include the presidency, the federal legislative (128 Senate seats and 500 Lower House seats including direct and indirect representation), as well as 31 out of 32 local legislatives, and 9 governors (out of 32 states). Over 1500 municipal governments as well as Mexico City’s 16 districts will also be up for election. The vote will be held on the first Sunday of June (June 2nd), and the new president will take office on October 1st, 2024 (as opposed to December 1st, as used to be the case).

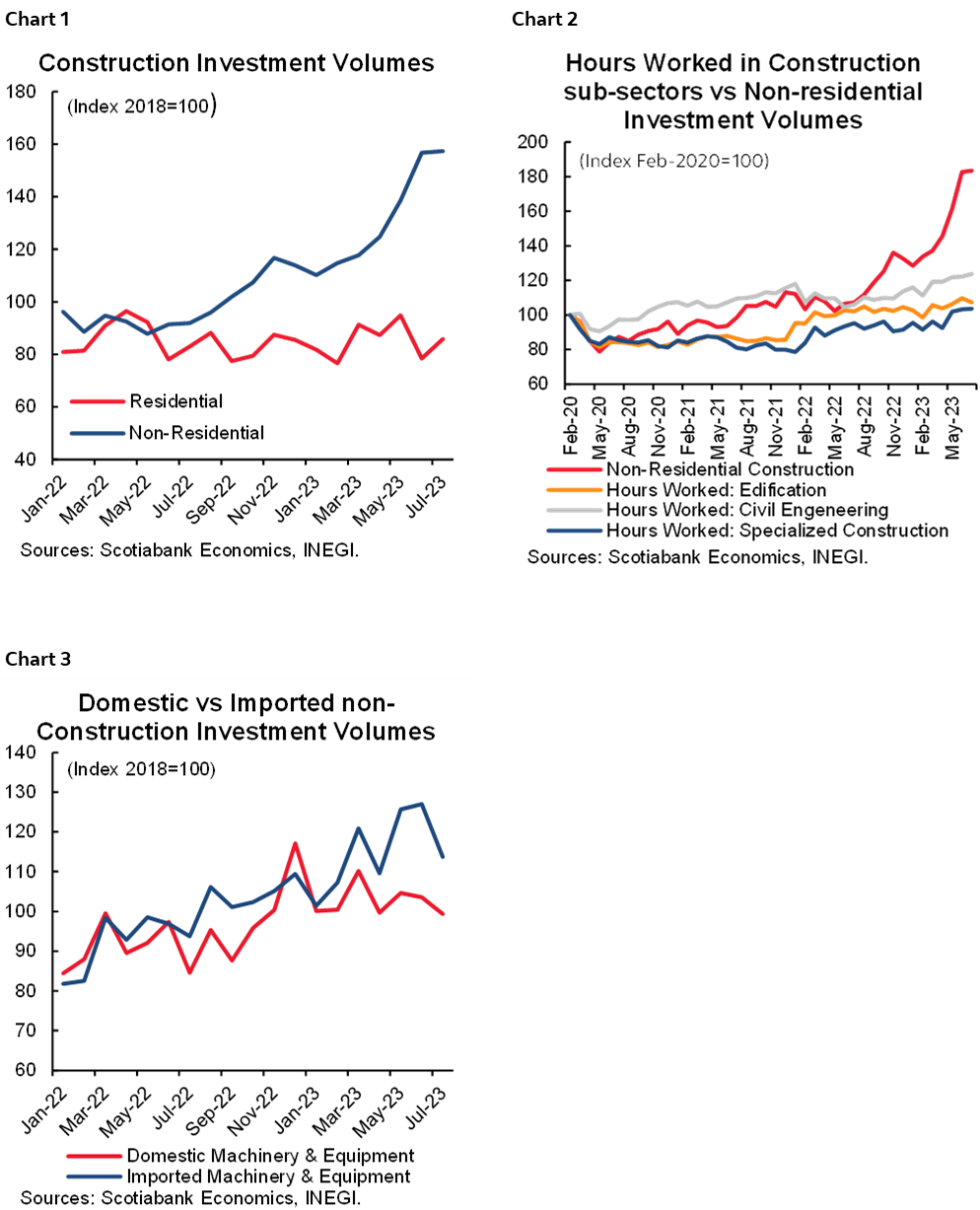

The main contenders for the presidency are AMLO’s protégée and former Governor of Mexico City, Claudia Sheinbaum. Her main rival will be Xochitl Galvez, who is somewhat of an independent candidate representing the main opposition coalition, the Fuerza y Corazon por Mexico (Strength and Heart for Mexico) which includes the center-right PAN, the centrist PRI and the center-left PRD. The other main contender was supposed to be the governor of Nuevo Leon, Samuel Garcia, but he has now withdrawn as the Movimiento Ciudadano (Citizens Movement) candidate to keep the state governorship, leaving the MC candidacy in an uncertain state. Polls taken at this stage have historically not been very good predictors of electoral outcomes, yet Morena’s “pre-candidate” Claudia Sheinbaum holds a strong lead at the start of the pre-campaign period according to the latest Mitofsky poll (chart 4).

The different parties involved in the 2024 contest will have a large platform to communicate their plans, with 52 million advertising spots approved for the electoral process, 30.5mn of which for the political parties and the remaining 21.6mn for electoral authorities. Out of the advertising spots allocated to parties, the governing Morena coalition will have 8.6mn, the PRI 5.4mn, PAN 5.3mn, MC 3.1mn, PVEM 2.8mn, PRD 2.4mn and PT 2.3mn. These ads could give us a glimpse into the platforms of the various candidates and parties. Overall campaign spending has historically boosted activity, with the three quarters heading into an election historically showing above-trend growth of over 1 percentage point. This could be amplified given the larger than usual spike in planned public spending this time around.

Although, informally, we are already about halfway through the electoral process (the unofficial candidate selection process kicked off almost a year before the June 2024 election), officially, we are only about 2 months into the election. The official key dates to keep in mind are:

- October 5th, 2023 was the last date for parties to announce the process for Candidate selection.

- Pre-Campaigning started November 20th and lasts until January 3rd. During this period, parties can only run ads aimed at party affiliates.

- Candidate selection for the different direct representation positions is set for January 24th at the latest, and for indirect representation positions by January 31st.

- Electoral platforms must be registered during the first 15 days of January (we can get a clearer picture of policy priorities here, but some of the platforms could be vague).

- The formal campaign process will stretch from March 1st to May 29th, followed by the electoral blackout from May 30th to June 1st.

- The 2014 Political Reform had left open the possibility of 2 Legislatives operating simultaneously in August 2024 due to an error, which has now been corrected. The new Legislative will now convene on September 1st, 2024. Given the new president won’t take over until October 1st, there is some speculation that AMLO could try to push through some of his pending legislation if his party secures a Constitutional Majority in the upcoming election.

- The new President of Mexico will now take over on October 1st, as opposed to December 1st, which was the previous norm. This means AMLO would have a shorter window to approve legislation if the vote goes in his coalition’s way. The early presidential takeover could also mean that the “spending slump” that sometimes takes place when the country has a government transition could come early.

KEY QUESTIONS FOR PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES

We think that from the perspective of investors, there are two key questions that need to be answered as we head into the government transition. It’s possible that these two questions will not be fully answered until a new government takes over, but hints on the different plans could start emerging around some key dates—including in January when campaign platforms are announced. In addition, we may get a better sense of their goals once we see the electoral teams and key experts in each candidate’s campaign. In our view, the two key issues are: power supply/generation, and Mexico’s fiscal trajectory.

1) Power supply and generation plans

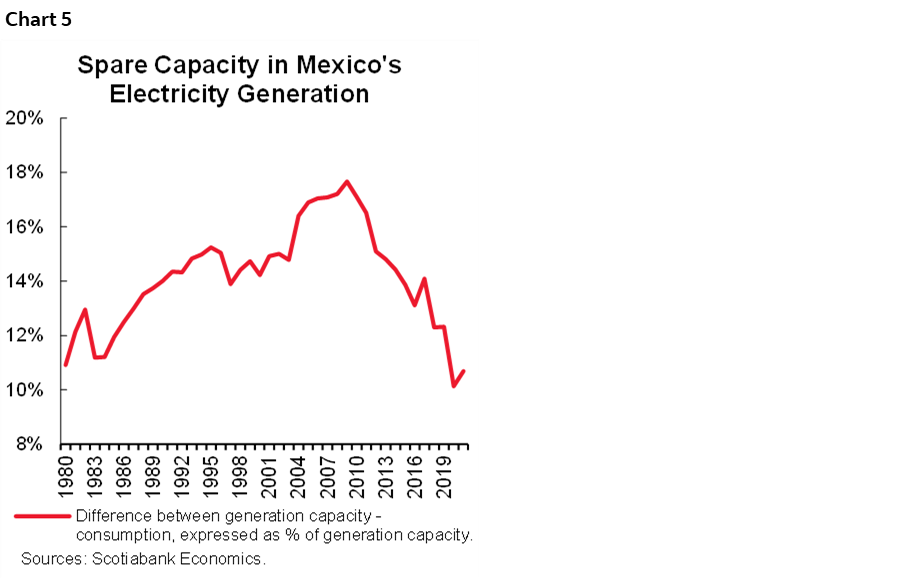

As we have noted in the past, one of the key challenges limiting Mexico’s manufacturing sector’s expansion is the capacity of the power sector to keep up from both a generation and transmission standpoint (the manufacturing sector consumes around 55% of the country’s power). Spare generation capacity sits close to multi decade lows, and the implementation of the 2013 energy reform is frozen (chart 5). AMLO failed to reverse the 2013 reform from a constitutional standpoint, but he reversed it at the legal and regulatory levels. Defining plans for the power sector for the 2024–2030 period will be key to allow the manufacturing to truly tap its potential (water scarcity is another key element, and a growing concern in recent meetings we’ve had with companies from different sectors and of varying sizes). We’ve highlighted that private participation in Mexico’s power sector was possible even pre-2013 reform with the use of PIDIREGAs (a PPP structure used in the period post 1994 crisis). However, if the PIDIREGAs path is followed, the structure of the contracts would need to be reviewed to adhere to new practices.

2) Plans for fiscal trajectory

As we’ve previously discussed, the 2024 budget shows a material widening of the PSBR (the wide definition of the fiscal deficit) to 5.4% of GDP, with fixed investment as a share of GDP falling. Rising spending and falling investment imply that the increase in spending will be difficult to cut as the bulk of the spending increase is allocated to social programs (and some current spending). AMLO passed legislation at the Constitutional level that protects his social programs from spending cuts.

Mexico will have some space for funding this larger deficit as the increased inertial deficit is almost identical in size to the increase in the assets under management (AUM) of the domestic pension fund system that resulted from the rise in employer contributions during the current administration. In addition, we don’t anticipate a relaxation in foreign investment limits imposed on pension funds, meaning that the bulk of the increase in AUMs will be “stuck” in Mexico.

Although this demand from domestic pension funds would give Mexico some additional room to fund itself for longer, it may eventually put at risk Mexico’s investment grade as it would allow public debt to balloon. In turn, Mexico’s weighting and inclusion in some benchmarks could be impacted—which would then apply additional pressure on debt funding.

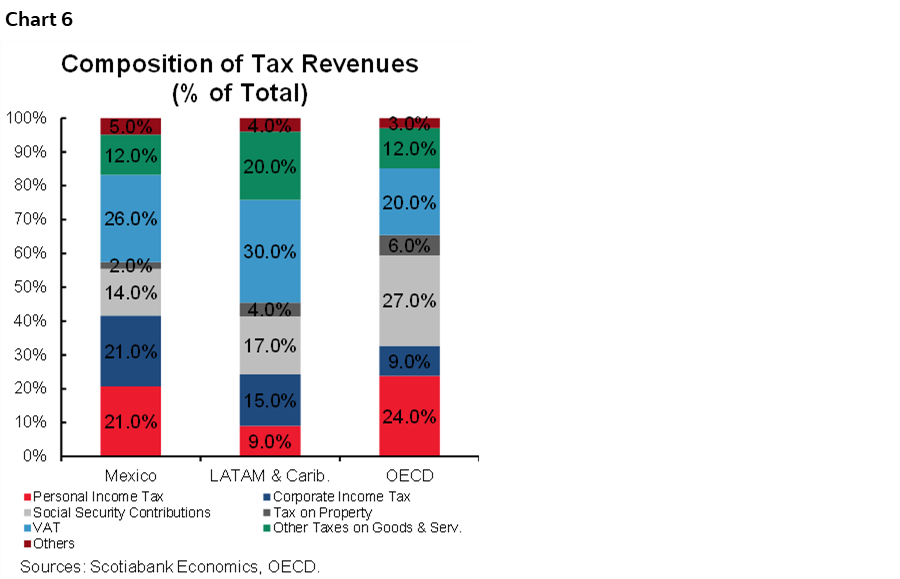

Hence, the better scenario is for the incoming administration to address the fiscal situation with one/both of a tax or broader fiscal (spending and tax) reform. Looking at Mexico’s tax structure relative to the rest of LATAM and the OECD, taxes on corporate income in Mexico are high (one of the factors we believe weighs on private investment), while social security contributions and property taxes are low. Mexican personal income tax, property tax, and VAT revenues combined account for the lowest share of GDP among LATAM and OECD countries—though these taxes are unpopular and are usually difficult to implement (chart 6).

With all of this in mind, we see a relatively benign inertial scenario in Mexico from a macroeconomic data standpoint, with growth still robust, and inflation and interest rates gradually easing. However, we anticipate that the first half of 2024 will be easier to navigate than the second half, not only in terms of macro data, but also in terms of political stability. We see an unusually wide set of risks around these scenarios, largely driven by the uncertainty surrounding elections in both the US and Mexico, and the wide range of possibilities for how the key issues will be addressed by incoming administrations.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.