Mexico’s presidential election will finally be held this Sunday, after an almost year-long electoral process; the formal campaign period kicked off in March 2024, but the pre-campaigns and the intra party processes began almost a year prior. The election will not only institute a new President (at this stage it looks like Mexico will have its first female president), but also a full refresh of both houses of Congress, 9 state governors (including the important Mexico City), 31 state legislatures, and close to 1,900 municipal governments.

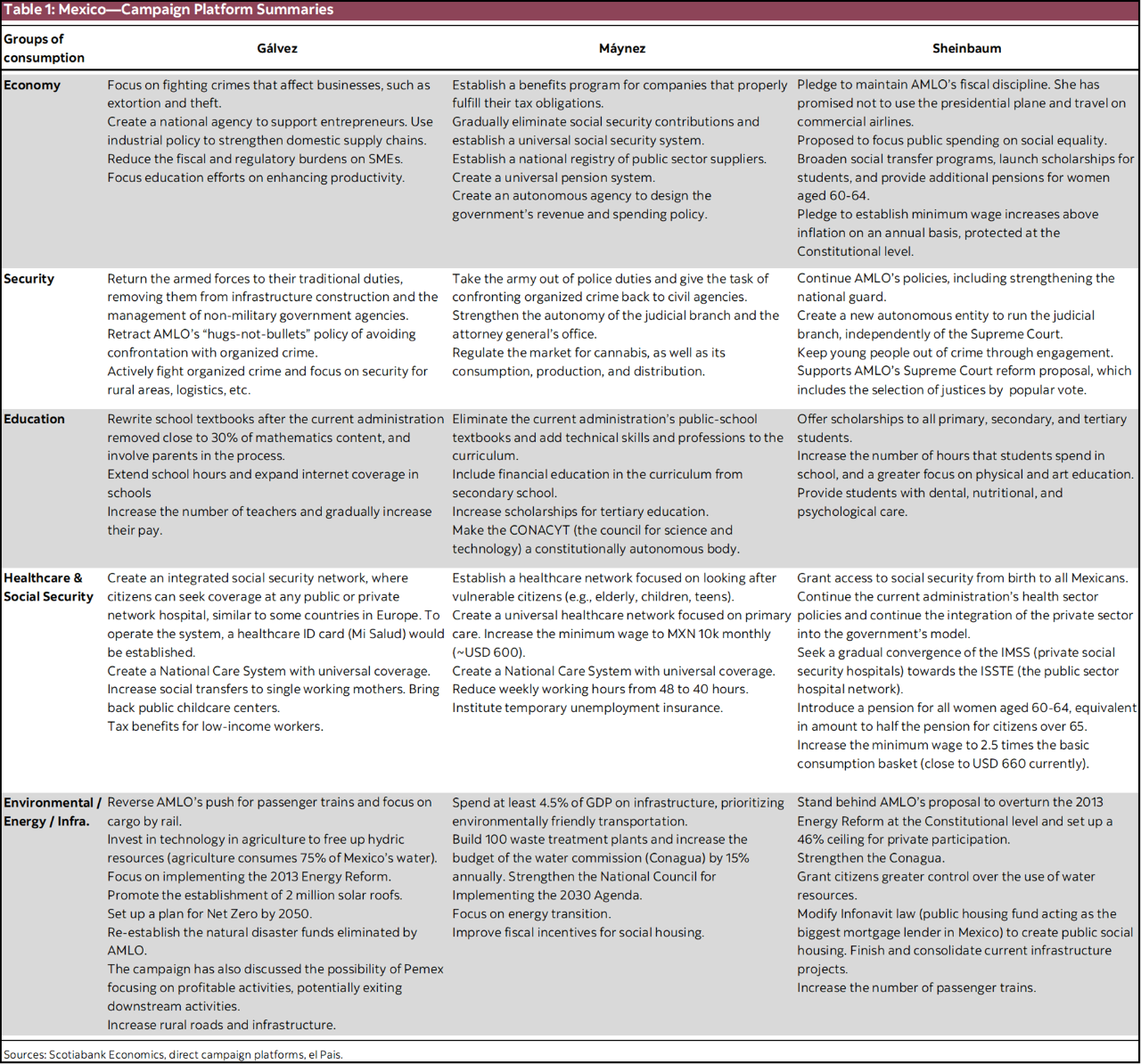

Despite lengthy campaigning, it’s been hard to sort through the content of the parties’ different platforms to garner what these are about, as the campaign has partly been pitched as somewhat of a referendum on the current administration. To varying degrees, the campaign platforms are scant on detailed proposals, but between the platforms and the various campaign events it’s possible to break down some of their key elements proposed. The incumbent party’s platform (Sheinbaum’s) has mostly pledged continuity with respect to AMLO’s government. The two main opposition platforms have pledged continuity for AMLO’s social transfers, but have diverged in some important areas—although here again specifics are wanting (table 1).

One key element which has been generally left out of discussion has been addressing the fiscal deficit that the next administration will inherit, after the current government budgeted a surge in the broad definition of the deficit to 5.9% of GDP.

At this stage in the game, voter polls and poll-of-polls suggest that Sheinbaum has a strong lead in the election (20–30 percentage point lead in the Oraculus.mx and Bloomberg poll-of-polls), yet several political analysts highlight that looking at recent state level election results suggest that the contest is materially closer than polls suggest. The margin of victory of the election will likely be closely monitored, particularly for two reasons: 1) on the immediate aftermath because a tight margin is seen as more likely to lead to post electoral conflict, and 2) the importance of legislative majority thresholds for policy implementation. Some key thresholds include:

- The Expenditure Decree is approved by 50% + 1 vote in the Lower House.

- The Revenues Law (which includes the tax bill and debt program) and Economic Policy Guidelines (macro assumptions of the budget) is approved by 50% + 1 vote in both the Lower House and the Senate.

- Passing legal changes requires 50% + 1 vote in both the Lower House and the Senate.

- Constitutional Amendments require a vote of >2/3 in both houses, plus a majority of State Legislatures.

However, there are arguments that in the case of a Morena victory, the importance of reaching the Constitutional Reform threshold is heavily reduced by the so-called 4th Supreme Court Justice argument (explained in local journal Nexos here). At the end of 2024, a seat will become vacant on the Supreme Court of Justice of Mexico. If Morena’s candidate, Claudia Sheinbaum, wins, it would be her turn to designate who occupies that chair. Depending on who is elected, if it is someone who gives unconditional support to the Federal government (as the three ministers: Loretta Ortiz, Yasmín Esquivel and Lenia Batres are considered to do), the government would have an unconditional block of four justices in the Supreme Court. With this, this block would have the ability to block any unconstitutionality ruling. This implies that, de facto, the government could carry out reforms such as the proposed reform of the electoral, electrical and justice systems, and ensure that they come into force, even if they do not obtain a qualified majority.

Potential key elements for investors:

- Energy: The opportunity that the reindustrialization of the US economy and the consolidation of regional production chains represents for Mexico also entails some challenges among which is rising power shortages (Mexico’s idle capacity in electricity generation is at its lowest level since 1980). Part of the electricity generation problem is due to the uncertainty that the sector currently faces in its regulatory framework, which has put the brakes on investment in both transmission and generation. Before the reform of the sector in 2013, private players increased their participation in generation to around 30% of capacity, mainly under the figure of PIDIREGAS PPPs. Subsequently, with the 2013 reform, private generation and ownership in generation opened, and the participation of the private sector rose to more than 50% of the installed capacity, with a strong boost to renewable energy, including that financed by funds from Canadian pensions (CDPQ, OTPP, PSP, etc.) and companies (TransCanada). However, after the victory of López Obrador in 2018, he tried to reverse the 2013 constitutional reform, but failed, leading to absence of certainty over the legal framework that regulates the sector.

Given the delay that has accumulated in both generation and transmission capacity, this issue has become critical in the electoral cycle. Candidate Galvez’s campaign has suggested that, if she wins, she will return to the application of the 2013 reform, which is very likely to see a significant recovery in private investment in the sector. On the other hand, Sheinbaum’s campaign has suggested that they would formally seek to end the 2013 reform at the Constitutional level, but that the sector would not be closed to private investment and that a 46% ceiling on the percentage of generation is likely to be applied to the private players. We interpret Sheinbaum’s message as suggesting that some form of PPP scheme will be introduced, possibly under the build-operate-and-transfer modality. This could lead to a significant recovery in private investment in the electricity sector—as long as her administration is willing to seek middle ground with private players.

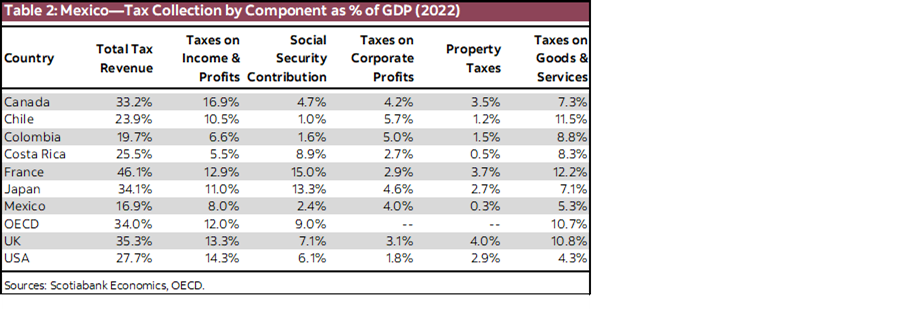

- Fiscal: As we noted earlier, the incoming administration will inherit an important fiscal challenge, as the outgoing government’s broad definition of the deficit (the PSBR) is budgeted to close at 5.9% of GDP. As is typical in a Mexican electoral process, neither campaign has been willing to speak about the potential introduction of new taxes (in Mexico that is seen as political suicide). Looking at Mexico’s tax collecting structure its apparent that corporate tax collection increases would harm the country’s competitiveness (corporate tax collection is already high, even more so taking into account close to 50% informality). Sales & goods tax collection is low, but rising VAT in Mexico has proven extremely hard politically in the past. Social security contributions, although low as a share of GDP are already rising substantially due to AMLO’s pension reform, through which employer contributions will rise from just over 2% of worker’s salaries to 11%. This leaves Mexico’s very low property tax collection, but in the country that is a municipal tax, and hence there is some speculation that the Federal government could introduce asset taxes (potentially only on real estate holdings, but it could also apply to broader assets/wealth). Finally, last week the FT reported that the government is considering introducing taxes on bank’s profits. Given the lack of formal discussion of this issue, this is but speculation at this point, but some form of tax reform could become necessary to stave off threats to Mexico’s credit ratings (table 2).

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.