Canada’s Federal Finance Minister provided a first multi-year peek at the impact of the pandemic on the Canadian economy and its finances today in her Fall Economic Statement 2020.

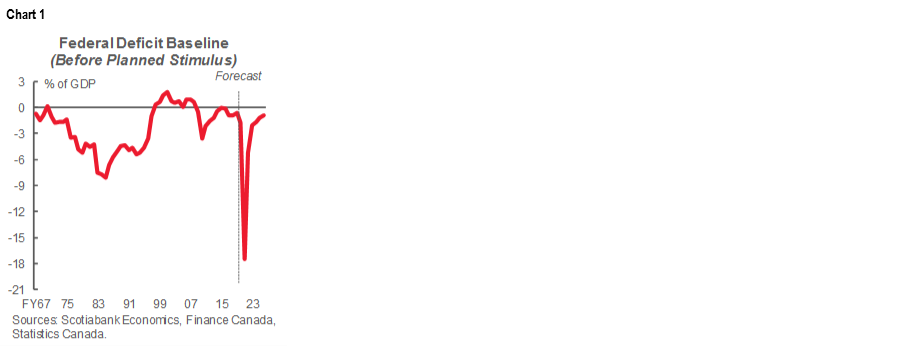

The deficit is set to soar to $381 bn (17.5% of GDP) in FY21—an increase of about $40 bn since July estimates (chart 1). At the same time, the government acknowledges it could be as high as $400 bn under alternative scenarios of extended and/or escalating COVID-19 cases.

The blow to government revenues contributes to a quarter of the shortfall, while COVID-19 spending will add another $275 bn of deficit financing this year. The bulk of increases in pandemic spending had already been announced—but not costed—prior to the update, whereas new announcements reflect about $25 bn. This includes a $17 bn top-up to the wage subsidy program to bring its coverage back up to 75% for the remainder of the fiscal year.

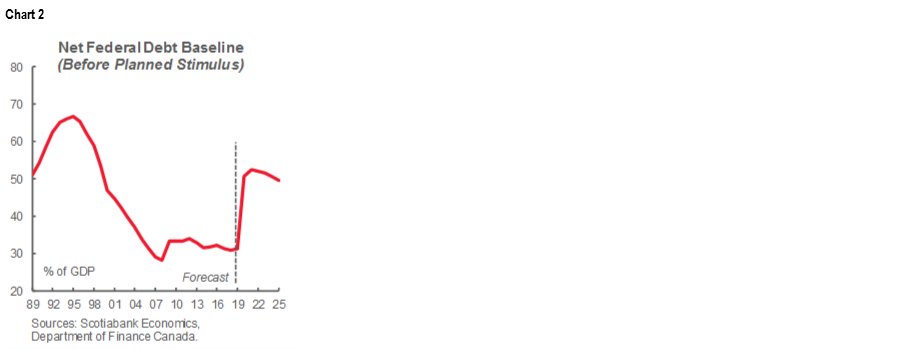

Debt as a share of the economy is expected to swell to 50% this year, peaking close to 53% in 2021 and declining thereafter (chart 2). But this is only a baseline that does not incorporate a new “stimulus” package of up to $100 bn promised over the next three years that would see debt soar to around 58% of GDP by 2024 under various scenarios.

The new stimulus package will be designed in the coming months with an intent to “jumpstart” the recovery. Its withdrawal would not be time-based, rather contingent on closing the output gap, loosely defined in terms of employment metrics. These so-called “guardrails” will guide fiscal policy until the economy has recovered and the government will then “return to a prudent and responsible fiscal path”.

Markets are likely to temporarily adjust to the implied bump in expected federal borrowing requirements (although an abundance of scenarios leaves this open to a wide range of interpretations), but this will be digested in an environment where global drivers are largely shaping bond market dynamics.

AN UNCERTAIN AND UNEVEN ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

Canadian Finance Minister Freeland provided a first multi-year outlook since the onset of COVID-19 in the 2020 Fall Economic Statement. The economic outlook is sobering, but not surprising. For fiscal planning purposes, real GDP is expected to contract by 5.8% in 2020, followed by a 4.8% rebound in 2021 before declining progressively to 1.9% by 2025. As per tradition, this is informed by the average of private sector economists’ forecasts, admittedly somewhat stale now, six weeks on. Economic scenarios illustrate the margins of uncertainty. In a scenario of escalated restrictions, the 2021 rebound would be an anaemic 2.9%.

While these headline projections have not changed substantially since the July update, drivers underpinning the forecasts have shifted. Estimates for the Q3 rebound continue to climb higher as official data trickles in, but second waves—though always expected—have necessitated tighter restrictions than anticipated in major cities and regions across the country. In recent weeks, bad-news coverage of mounting COVID-19 cases is competing with vaccine advancements and greater certainty on US political developments that have been buoying financial and commodity markets.

The update goes to lengths to emphasize the unevenness of impacts. In particular, it notes that sectors where physical distancing is challenging continue to be the hardest-hit, including travel, tourism, food and accommodation, and some retail and service industries. More targeted shutdowns in second waves should serve to minimize the overall drag on growth, but would reinforce the variable-speed recovery for those businesses and households relying on these sectors for income.

THIS YEAR’S DEFICIT TO SWELL FURTHER

A deficit of $381 bn—or 17.5% of GDP—is now projected for FY21. This represents about a $40 bn increase over July projections. Reflecting the high degree of uncertainty in program uptake, early COVID-19 spending estimates of $230 bn at the time of the July snapshot were scaled down, while new measures amounting to $80 bn were added, but with a net impact bringing pandemic spending to only $275 bn this year.

The bulk of this increase was largely guided ahead of the update. In the weeks following her appointment in late August, Finance Minister Freeland adapted and/or extended the key pandemic measures from first waves: second-round employment benefits through September 2021 (via the new Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB), Employment Insurance (EI) program changes); the wage subsidy program through June 2021; rent subsidy reforms; and increases under the Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA) for small businesses.

The update, for the most part this fiscal year, costs these already-announced items. An estimated $55 bn in spending line items this year were already announced prior to today’s update, whereas new measures tallied about $25 bn. The bulk of new spending is consumed by a top-up of the wage subsidy to 75% through to the end of the fiscal year at an incremental cost of $15 bn, a $2.1 bn increase to rent subsidy and lockdown supports, and a host of smaller amounts such as another top-up to the Canada Child Benefit. The government will also be launching yet another loan program for hardest-hit businesses through the Highly Affected Sectors Credit Availability Program for amounts up to $1 mn, while it will continue to reform the Large Employer Emergency Financing Facility to enhance take-up among larger sectors most affected (namely, energy producers and airlines).

Then there is a lengthy list of smaller measures with more tenuous links to the immediate pandemic response or broader recovery. There are dozens of line items ranging from a couple of million to tens of millions for initiatives such as improving program and procurement integrity to improving outreach with Canadians. It also incorporates a more substantive amount of $1.4 bn this year for compensation for supply-managed farmers. Modifications to the First Time Homebuyers Program were also announced for the most expensive cities, as was a tax on unused property by foreign non-resident owners. While these measures are designed to increase the affordability of housing, they are unlikely to have much of an impact. Changes to the First Time Homebuyers plan may actually be counter-productive.

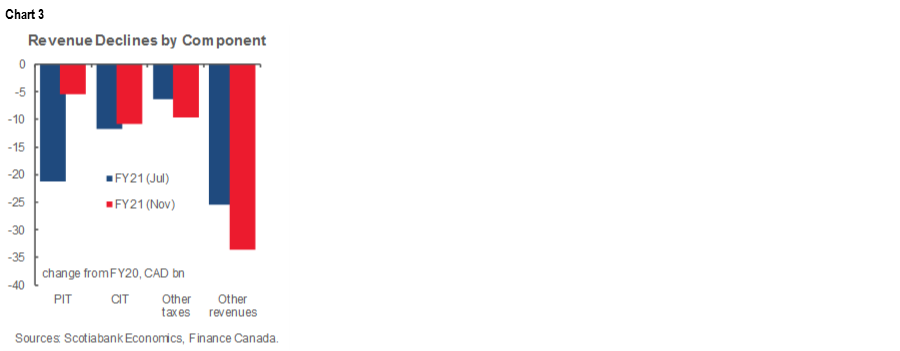

Finally, a substantial hit to government revenues rounds out deficit forecasts for the year. The fiscal shock to the balance sheet has deteriorated only modestly relative to July projections (-$5.9 bn), but this masks an improvement in personal income tax receipts offset by declines in other revenues. (chart 3). Corporate tax receipts will plummet by 22% compared to 2019, while personal income tax are expected to fall by a lesser 3%. Other revenues, including GST and crown corporation revenues, are expected to drop by 15% y/y. Revenue as a share of GDP is expected to dip to 12.6%.

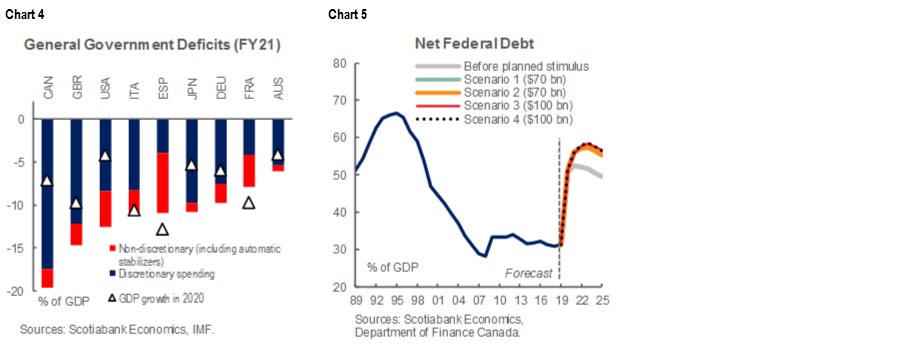

As big as this year’s deficit will be, governments around the world largely have a carte blanche for temporary COVID-19 spending. The IMF has been urging governments to spend—if they can afford it—to ward off a worsening outlook. Canada is set to provide the highest level of discretionary spending as a share of GDP (federal and provinces, combined) across all major economies (chart 4). This should, for the most part, be a good news story as it has helped engineer a near-term economic turn-around at a faster-than-anticipated pace despite the double shock through commodity channels. Furthermore, the federal government has borne the share of Canada’s costs which is also a positive as it has greater fiscal firepower and lower borrowing costs than provinces for the most part. But it must prove temporary to remain a positive and today’s update casts some doubt in this regard.

A BASELINE ALREADY STALE

The federal government has set out a “baseline” for the deficit path absent further stimulus. It profiles shortfalls of $121 bn (-5.2% of GDP), and $50 bn (-2.1% of GDP) in FY22 and FY23, respectively, and sees deficits continuing to decline over time to less than 1% of GDP by FY26. This baseline incorporates about $15 bn over five years in new outer-year commitments under the guise of ‘building back better’. Pledges are diverse: $2.6 bn (over five years) for home retrofits, $2.5 bn for reconciliation, $2.3 bn for a one-time Canada Child Benefit top-up in 2021, $1.3 bn for tree-planting, and the numbers get smaller and smaller.

The update makes only a modest down-payment on an eventual green recovery, with presumably (hopefully?) more measures to come. A package of green items amounts to less than $5 bn over the next five years as itemized in baseline projections. An ambitious, yet reasonable, green recovery plan would more likely be in the order of $10 bn per year. There is likely no binding limit on what could be done to affect a shift to meet the 2050 climate target and eventual interim goals. However, $10 bn would reflect an ambitious target from a practical perspective for a public investment-driven approach, given past challenges at executing against plan on major infrastructure pledges.

Similarly, pledges towards childcare underwhelm expectations. The update provides only modest funding for the creation of a Secretariat to deliver on the broader mandate in the order of $20 mn over five years. The pandemic has amplified the economic impacts of (the lack of) childcare on female labour force participation, though the issue has persisted for decades. The business community, in particular, has added its voice in calling for action in recent months. Small steps announced today are therefore welcomed, but protracted, multi-year negotiations with provinces lie ahead with a reasonable risk that priorities or governments shift before yielding measurable results. Provinces have also largely been silent on this issue, emphasizing other pressing priorities. This shop had urged more immediate, market-driven approaches that could have provided critical support in the near-term to struggling families, while also underpinning the recovery. Owing to this missed opportunity, working parents will have to wait for childcare relief for the time-being.

A FISCAL OUTLOOK EVEN MORE UNCERTAIN

The government’s own fiscal baseline is immediately rendered hypothetical with a pledge to spend “up to $100 bn” over three years. In their own words, “this stimulus plan will be smart, time-limited investments that can act fast to jumpstart the recovery and have long-run value by creating shared prosperity, improving Canadians’ quality of life and powering our green transformation. The government’s growth plan will include investments that create good, middle class jobs and unleash private spending in the short-run, and that also help us strengthen Canada’s competitiveness in the long-run. This will include growing a green economy, investing in infrastructure that supports our communities, workers and flow of goods, and supporting inclusive participation in the workforce.” Lofty goals, but no details.

The government lays out four illustrative fiscal paths for new stimulus spending. These include the allocation of $70–100 bn over three years with very broad ranges in possible fiscal impulses over that time frame: between $20–30 bn, $30–50 bn, and $10–30 bn in FY22, FY23, and FY24, respectively.

It justifies a range of stimulus scenarios by introducing the concept of fiscal “guardrails” that will provide contingent-based conditions that will guide when stimulus will be wound down. The update explains that the eventual withdrawal of support would not be time-bound, rather condition-bound. It plans to track progress against several indicators, mostly employment-related, including the employment rate, total hours worked, and the level of unemployment. Again, in their own words “these data-driven triggers will let us know when the job of building back from the COVID-19 recession is accomplished, and we can bring one-off stimulus spending to an end, returning to a prudent and responsible fiscal path, based on a long-term fiscal anchor we will outline when the economy is more stable.” However, there is no clarity on what thresholds would be ‘acceptable’, while lagging indicators could also bias an overshoot.

VARIOUS POSSIBLE DEBT TRAJECTORIES

The baseline fiscal path projects federal net debt peaking at 52% in its hypothetical baseline, but—under all of the stimulus scenarios—debt escalates closer to 58% by 2024 before beginning to reverse course. At face value, the eventual recovery plan’s stated intention is to boost growth (i.e., the denominator), not just the numerator, which would suggest a steeper downward slope in outer years. But, again, details are insufficient to judge this, while messaging implies a spending bias with less-than-binding constraints.

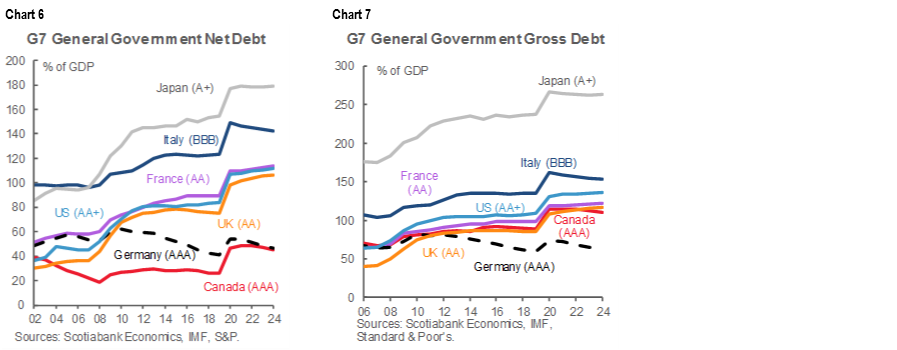

Nevertheless, Canada should still have the lowest net debt among peers. The IMF had projected Canada’s general government net debt (i.e., federal plus subnational debt after netting out assets) to be the lowest among G7 countries at around 46% in 2020 in October, while its general government gross debt would be among the lowest (charts 6 & 7). This update ticks up debt levels, but they would still be below other G7 peers (and the next closest contender, Germany, is likely to face upward fiscal pressures also, in light of more severe second waves). This is not a defense of profligate spending, rather a less-than-perfect benchmark when assessing potential funding risks in global markets where relativity matters. That said, Canada does not benefit from reserve currency status that provides a greater debt tolerance for some.

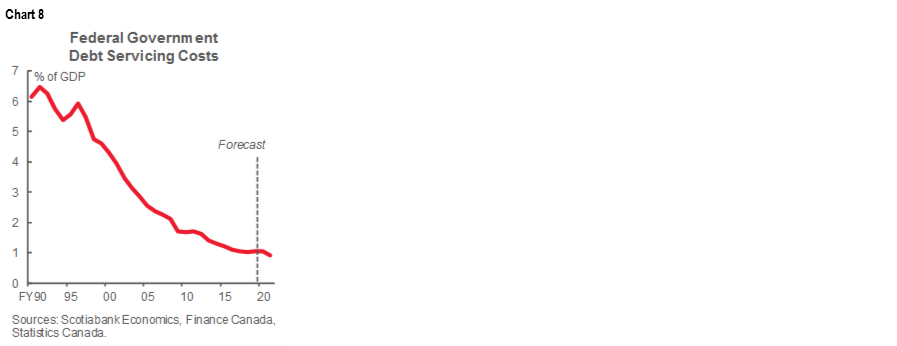

Debt servicing costs should be top of mind for policy makers as a more practical binding constraint to elevated debt levels. The government continues to project debt service costs to come in below 2020 levels, despite burgeoning debt. With long term real interest rates expected to remain low at least over the course of the recovery, debt servicing costs as a share of GDP are expected to increase only modestly in 2020, but still around 1%. Debt servicing should not impose the same degree of hardship as past periods of elevated debt burdens when interest payments as a share of GDP approached 6% (chart 8).

However, recent market rallies on the news of vaccines and US developments flag how quickly outlooks could potentially change. It is feasible that a faster-than-anticipated recovery fueled by any number of developments, but for the sake of argument, a larger-than-anticipated US stimulus package and a consequent faster policy rate tightening path and/or stronger-than-expected inflation, could drive up yields faster than baseline expectations. This would translate into higher costs of government funding though—even in such an upside scenario—the potential uptick in effective rates on government debt would still be very low relative to historic highs.

MARKET TO ABSORB SIGNALLING...FOR NOW

Borrowing requirements for FY21 are unchanged, though the composition of needs has shifted. The government still anticipates total financing requirements of $703 bn in FY21, but increases in deficit financing are offset by reduced needs for off-budget items. In particular, the July update had conservatively provisioned for various pandemic programs delivered by crown agencies including BDC, EDC and CMHC’s MBS. The uptake has been far less than provisioned, warranting a downward revision. The government also shifts more back financing activity to short term instruments this year, with projected bond issuance scaled back to $374 bn (from $409 bn) and estimated T-bills outstanding by March 31 to increase to $329 bn (from $294 bn).

Markets have likely been anticipating more fiscal activism in federal fiscal policy prior to the update. Policy signals—both soft and hard—have largely been uni-directional since Parliament resumed. On the other hand, federal bond issuance had slowed in recent months, presumably in light of assumed lower financing needs related to crown corporations, which may have countered that signal. Markets, so far in this pandemic, have tended to only fully price in federal fiscal developments when concrete measures are announced. There may therefore be some near-term adjustments, with modest sell-offs by way of a recalibration to larger expected deficits in outer years, but the fiscal path is so tenuous at this stage that any reaction will likely be muted. Furthermore, these are being digested into global markets that are rapidly evolving, not to mention escalating COVID-19 cases and diminishing soft Brexit hopes, set against mounting optimism around vaccine developments.

For now, Canadian federal debt should remain attractive in global markets where the majority of sovereign debt is negative-yielding. Massive COVID-19-related spending was broad-based around the world with markets and rating agencies looking through this year for the most part. Market spreads on Canadian federal government debt have remained relatively tight. Moody's reaffirmed Canada’s top tier borrowing status earlier this month, DBRS in September, and S&P in July. Fitch had downgraded Canada at the onset of the pandemic—with no material market impact as its sovereign downgrades were broad-based. Canada still ranks highly on its strong institutional and policy fundamentals.

Global developments will likely continue to drive bond market appetites over the medium term, including for Canadian sovereign debt. As with any economic recovery, the enthusiasm for bonds can be expected to wane over time with markets demanding higher premiums to account for growth and inflation risk. The federal government has slightly lowered its projection for the 10-year government bond rate this year and next (to 0.7% and 0.9% in 2020 and 2021, respectively). It projects a steady increase to 2.4% by 2025. A word of caution, though, these forecasts only reflect developments as of mid-September, and, obviously, would not take into account new spending implied today.)

Another word of caution is that strict bond yield comparisons across similar maturities of other country sovereign debt may exaggerate the relative attractiveness of Canadian dollar debt. The CAD has appreciated by less than other major currencies to the USD since March, while non-commercial net positions presently maintain a short position in CAD despite recent strengths. The cost of hedging against further CAD depreciation relative to the USD also remains higher and has improved by less than for currencies like the sterling, yen, or euro. It is unclear why the Canadian dollar has behaved this way since global markets began to improve after March, though there are multiple plausible explanations for these observations. One possibility is that currency markets are less sanguine toward the risks of buying Canadian debt than relative yields may suggest.

These risks underscore that Canada should not rest on its laurels. Given the non-linearity in market reactions, the federal government will need to ensure it is not behind the wave as countries start consolidating balance sheets in the wake of this crisis. It has necessarily extended pandemic programs for the most part, but this has only deferred demonstrating credible exits. It has upped spending in outer years, but has not convincingly demonstrated how these added deficits will address structurally slow economic growth versus simply adding to structural deficits. And, the higher fiscal impulse will feed into the Bank of Canada’s assessment in its own potential policy responses. All of this to say, further movements in yields in federal government debt will be informed by variety of factors—domestic and global. The government only has influence over the former.

TAKING A STEP BACK

The federal government has set out a path of moderate deficits over the planning horizon with little detail to assuage growing concerns about escalating debt levels. Some of the new spending will necessarily support harsher second-wave impacts, but its cost-benefit analysis rests on assumptions that tweaks to early supports will be better-targeted this time around. Meanwhile, the bulk of outer-year spending is intended for a much-needed recovery plan, but its credibility is arguably undermined by a rebranding around a vaguely-defined “stimulus” plan. Poorly-demarcated, it leaves the door open for a range of spending priorities.

We see some pressing policy challenges ahead for the federal government—as it turns to the preparation of its full budget—where the update is vague, if not wanting:

- Pandemic-response policies need to be better-targeted and support transitions to a post-pandemic economy. In October, almost half a million Canadians were considered “long-term unemployed”—or out of work for more than 27 weeks— essentially since the pandemic began. Policies that help these Canadians back into the labour market, possibly in different sectors, will be critical to Canada’s growth potential. It is unclear that the CRB alone can do this. The million-job pledge will have some heavy lifting ahead. Similarly for business supports, the focus should shift from shielding companies to helping them adapt to a new environment.

- The eventual withdrawal of pandemic supports needs to be credible. The tone needs to shift from ‘we’ve got your back’ to one that positions the government as a supportive partner in necessary transitions in order to start normalizing expectations around government support. This will be particularly pertinent in the design of a revamped EI program over the coming year. The CERB served its purpose as an expeditious, but blunt stabilizer to a sudden-onset shock, but it also had its shortfalls. The new CRB has yet to demonstrate if it will achieve an ideal balance between income replacement and incentives to work. And neither program, by design, has integrated any concept of self-financing that will ultimately be an important component of a new EI program. Without this, it risks permanency in government-backing of income protection.

- Canada’s debt is not sustainable over the long term unless provincial levels are as well. Markets and rating agencies assume an implicit federal backing of provincial debt. One-off transfers to provinces were necessary in the name of expediency, but a longer term structural shift is likely needed that requires cooperation and coordination. Uncosted modifications to the Fiscal Stabilization Transfer will no doubt also be welcomed by provinces this year. But unconditional transfers are not a guarantee alone for longer term sustainability and could further fragment the policy landscape across many federal priorities that rely on intra-governmental cooperation: childcare, pharmacare, infrastructure, labour market skills and training initiatives to name a few. And the discussion should be broader than expenditure-shifting, as provinces have been reluctant to take up revenue capacity given up at the federal level in recent years.

- The recovery plan needs to be just that. The Bank of Canada has estimated Canada’s growth potential will average 1% through 2023. Additional spending should be laser-focused on fostering some upside in that outlook. If sums notionally tabled today—i.e., a stimulus package of $70–100 bn over three years—were fully allocated to measures with highest multipliers over the medium term such as infrastructure or stronger labour force participation, this could be a substantial boost to growth over this time horizon. But if its eventual allocation resembles the smaller “Building Back Better” package detailed today, it is likely wanting in this regard.

- Finally, the federal government needs greater transparency and accountability around its fiscal plan. Most economists would agree that fiscal policy needs to be calibrated to economic conditions, but the guardrail concept falls short in this regard. It is poorly-defined and too vague at this point to either inform market participants when fiscal support will be withdrawn or to provide any real constraints to policymakers. Its lagged nature also raises a risk of running counter-cyclical fiscal policy well-beyond the recovery, exacerbated by the multi-quarter lead times for most fiscal measures. A reasonable fiscal plan would set policies within a broader framework of how debt will be managed—whether it is leveraged for growth or it is actively consolidated for the next downturn. This is what provides transparency and accountability. For example, there is still a high degree of opacity as to how an eventual stimulus package would be financed, raising potential tax risks on the horizon. Ultimately, credibility is earned by execution against plan, but, in the meantime—and particularly important in times of persistent deficits and escalating debt—setting limits on oneself is preferable to markets setting them for you.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.