- Canadians head to the polls on September 20th, less than two years since voters weighed in on national priorities.

- While the world may have changed dramatically since then, the issues on the table are remarkably similar: household (and housing) affordability, childcare, jobs, climate policy, and social supports.

- But there has been greater convergence on policy positions across party lines since then, with a bias towards more spending. The two leading parties alone propose over 150 new measures to tackle some key challenges, both with price tags coming in just above $50 bn over 5 years.

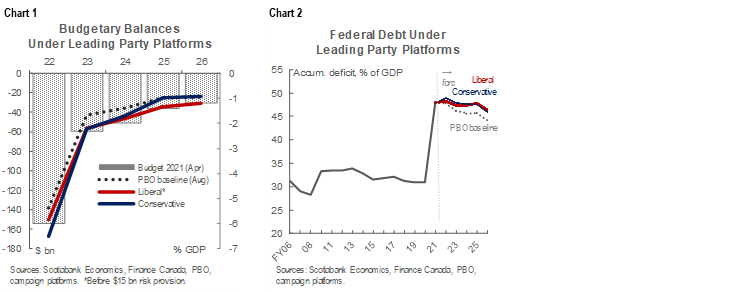

- Each would continue to run broadly similar deficits over the next five years—about 0.5% of GDP higher annually on average than those projected by the PBO heading into the elections (chart 1).

- Fiscal anchors are largely non-existent (at least meaningful ones) with both leading parties projecting modestly declining debt as a share of the economy over the horizon, landing about 2 ppts higher than PBO projections by FY26 (chart 2).

- Narrow (and variable) polling margins make an election call tough, but for market participants at least, the range of potential impacts are narrower given largely stay-the-course fiscal paths.

- Some policies—if enacted—may have modest sector- or region-specific implications, but markets rarely price-in election promises. A wait-and-see approach is even more likely in the context of an expected minority win that is fair game for either leading party at this point.

- Furthermore, outcomes will be digested in a rapidly-evolving environment where global drivers (and central bankers) are shaping bond market dynamics. And Canada still looks pretty good.

- Nevertheless, the next Finance Minister’s job will be all the harder with another $50 bn+ layered on top of last spring’s $100 bn into an economy that is well on its way to full recovery and that is already running up against serious supply constraints.

- A confluence of expansive fiscal policy (especially once provincial support is included) working against monetary tapering as the output gap closes could put even more pressure on prices and interest rates. In the end, this could hurt voters’ pocketbooks more than some of the proposed measures purported to resolve affordability issues for Canadians.

BACK TO THE POLLS

Canadians will elect the country’s 44th government on September 20th. Emboldened by Canada’s (relative) success at managing the pandemic, the current Prime Minister called this election less than two years since the Liberal Party won a minority mandate in October 2019. Any hopes of a pandemic bump have been fading over the course of the 36-day campaign. Support for the incumbent (Liberals) has waned since elections were called with the party now neck-to-neck in most polls with the opposition party (the Conservative Party of Canada).

Recall, the Liberals were reduced to a minority government in 2019 after holding a majority since 2015. In 2019, the party secured 155 seats of 338—and below the 170-seat threshold to claim a majority victory. Conservatives formed Opposition with their 119 seats, but the Liberals were able to maintain confidence through informal alliances with other left-leaning parties who held the balance of support.

At this point, another minority government outcome is highly likely—the big question is whether it will be led by the Liberals or the Conservatives. A Liberal minority would once again lean on the New Democratic Party (or other smaller parties) to garner enough support to pass legislation. This proved (and should prove) a relatively easy task, particularly in the context of the pandemic, where both left-leaning parties have a strong propensity to spend. But Liberal leader Trudeau has implied he might send Canadians back to the polls sooner than later in this scenario.

A Conservative win would also raise a degree of uncertainty. It would face pressure to shift (further) left on some policy issues to garner enough support needed to pass legislation (and maintain confidence). This time at least, money is not the issue with all parties prepared to spend. Policy principles will be the battleground on issues such as climate and childcare where the divisions are not so much if but how. Coalition-building will be a critical tool—and also a real threat—to governing under such a scenario with the Liberals and NDP waiting in the wings.

Only a majority win would reduce election uncertainty. Pollsters are not putting a high probability on this, but Canadian voters did defy polls in the most recent provincial election in Nova Scotia, giving the opposition party (Conservatives) majority reign (albeit under different circumstances).

There may be much fodder for political pundits to digest over the coming weeks (and possibly months), but there are arguably fewer implications for bond market participants. Even Canada’s centre-right Conservative party is closer to left-leaning parties in other countries and all parties have inched further left over the course of the pandemic as the public and markets alike have shrugged off debt-fueled spending over the course of the global pandemic.

PRIORITIES & PROMISES

Dominant economic themes across parties include further pandemic supports, household (and housing) affordability, childcare, and climate policy. All parties commit to providing continued support to get the country across the COVID-19 finish line with only policy tweaking (and a few pocketbook-pandering measures) distinguishing party platforms. Canada has provided among the largest temporary fiscal support in response to the pandemic and that will not likely change in the coming months. Last spring’s federal budget baked in an additional $100 bn in support over three years that has only started to flow.

Household (and housing) affordability is a permanent feature in Canadian politics. The pandemic has exacerbated persistent market failures: a chronic undersupply in housing that has driven prices up further for the 35% of Canadians who don’t own homes; and an under-provision of affordable, high-quality childcare that presents an obstacle for thousands of Canadian women. No party offers much long-term relief on the housing front given limited levers at the federal level (though a slew of marginal measures could stoke housing markets further). On childcare, all parties stand behind the issue, but differ substantially on how to address it (e.g., public versus market provision; funding to families versus provinces). In reality, likely a combination of both is warranted.

Climate policy is another common platform plank where there is some differentiation. The Liberals offer a stay-the-course plan with ambitious reduction targets (i.e., 40–45% emissions reductions by 2030) with carbon taxes carrying the brunt of the effort (topping out at $170 per tonne by 2030 from $40 today). Meanwhile, the Conservatives would relax targets (i.e., 30% by 2030) and rejig the carbon tax (capping it at $50 per tonne for consumers and $170 per tonne for industry if the US and Europe match the price). They are broadly aligned on sector-specific support including for cleaner grids, electric vehicles, green-retrofits, hydrogen and other clean tech. The other main federal parties (NDP, Greens and Bloc Quebecois) support aggressive climate action, which will surely matter when it comes to enacting policies in a minority government context.

Unlike past elections, all parties are generally united in the view that Canada needs to capitalize on the momentum behind the global climate transition that is underway. With the US now on side with other major markets such as the European Union pushing for more ambitious climate action (with potential trade repercussions for laggards), Canadian parties are more or less falling into line, in principle, at least. The key differences land on the means to get there and whether to be slightly-ahead or not-too-far-behind other major players such as the US. For businesses making multi-decade investment decisions, the credibility, clarity, and certainty of the climate policy landscape will be key.

Any rich debate on growing the economy has largely been absent. The two leading parties pledge to establish an equivalent to the US DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), committing $2–5 bn to establish a new government body. Both tinker on the margins of labour markets with “one million job” pledges, but in reality it will be the private sector that will likely deliver on this regardless of (or in spite of, in some cases) government interventions. Finally, both parties largely miss the mark on leveraging taxation as a tool for growth, pitting it against redistributive objectives (to be fair, the Conservatives promise a broad review but, for now, both parties propose a host of boutique tax measures that add to the system’s complexities and potential distortions).

DEFICITS WON’T DIVIDE THE VOTE

Leaders were all handed a fiscal windfall as they launched their campaigns. A stronger-than-anticipated recovery—particularly in nominal terms which matters most for government revenues and expenditures—translates into an improved deficit profile heading into elections. The Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) set the fiscal baseline in mid-August a full $86 bn better than April’s budget forecast over a five-year horizon. Growth revisions since then may have taken some of the wind out of the recovery: Scotiabank recently revised down its real GDP forecast by 1.3 ppts—to 4.8% in 2021—but, in nominal terms, growth is actually up modestly given hot inflation.

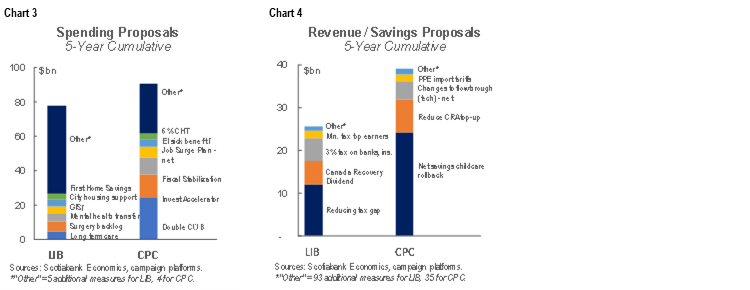

All parties are capitalizing on this boon, with spending likely to continue under all realistic election outcomes. On a net basis, there is barely a $1 bn difference between the Liberals’ $52.6 bn (over 5 years, not including $15 bn in risk provisions) platform and the Conservatives’ $51.4 bn plan. Numbers get a bit murkier when teasing out new spending versus new sources of fiscal space (e.g., new revenues or savings/cuts). The Liberals promise $78 bn in new spending (both expenditure-based and tax-based measures), while proposing offsets of $25 bn through various new revenue-raising measures. Meanwhile, the Conservatives up the ante with new spending commitments tallying $90 bn, but reduce the net cost largely through the roll-back of existing spending commitments that would net $39 bn in savings (charts 3 & 4). Ironically, the NDP platform comes in at the lowest net cost—$48 bn over 5 years—but it comprises of $214 bn in spending, offset by $166 bn in new revenue measures (with a high degree of uncertainty on the latter). While the NDP is not in contention to win, in a minority context its positions will likely matter.

The different approaches to provinces and sectors could have some bearing. The Conservatives would front-load transfers to provinces ($9 bn in FY22), providing some balance-sheet relief to oil-producing provinces, along with the 6% riser in the Canada Health Transfer (as requested by Premiers) that would only have a material impact beyond its first mandate. The Liberals provide a slew of conditional transfers (childcare, healthcare, long term care, etc.) amounting to over $20 bn over five years (plus the $30 bn including already-legislated childcare transfers). The degree to which these provide balance sheet relief to provinces would vary across provinces, in part, according to the degree they impose new funding pressures or offset existing ones. Similarly, different positions on pipelines, banking, and telecom sectors could have a bearing on specific parts of the economy to the extent they are enacted and how they would be implemented.

Otherwise, any differentiation between party planks on the bottom line is largely negligible. Both platforms would see, on average, an additional $10 bn per year added to financing needs over the next five years beyond the PBO’s baseline. For a $2 tn plus economy, that works out to less than 0.5% of GDP. This is not immaterial, but it is additive. A lower economic growth profile could add a few more tenths of a percentage to the annual balance, a not-unreasonable possibility given the high degree of uncertainty around the outlook over the next few years. (The PBO estimates a 1 ppt change in real GDP translates into roughly a $5 bn impact on coffers.)

It would be premature to give much weight to economic impacts of various platforms. Between one party’s heavy lean on social spending, another’s on various tax breaks, and both providing various sub-national transfers, the fiscal multipliers (i.e., the effect of spending on output) are likely underwhelming. Furthermore, the economic dividends would likely be eroded as the economy will be much further down the path to recovery by the time supports hit the ground (fiscal multipliers tend to be higher when economies are weaker). Finally, whichever party eventually wins, the politics of delivering on pledges will be sufficiently complex to warrant a more cautious approach to incorporating much impact at this point.

DEBT HERE TO STAY

Needless to say, no party is campaigning on reining in public debt. The federal government’s accumulated deficit stood at 48% of GDP ($1.1 tn) at the end of FY21 with the PBO projecting a gradual wane to 44% of GDP by FY26 on the back of modest economic growth in the order of 1.6% in outer years. The Liberals are sticking to their go-to fiscal anchor since 2015: keeping debt on a modestly downward trajectory as a share of GDP (never mind that the starting point is now 17 ppts points above pre-pandemic levels). And even then its interpretation has been fairly flexible; for example, its own fiscal path shows debt temporarily increasing in FY25 before bending back down). The Conservatives meanwhile pledge to balance the budget within ten years, but over a 5-year horizon present a debt profile that mirrors the Liberals’ given similar deficit paths.

Parties would have to work hard not to see declining deficit and debt trajectories over the horizon. The bulk of spending over the pandemic has been temporary, and while economic growth projections are mediocre—nominal growth projections still eclipse interest rate projections in the baseline scenario that should keep debt as a share of the economy on a downward trajectory...mathematically, though. From a political-economy perspective, with a growing population and aging demographics, politicians will have to work hard to ensure debt remains on a sustainable trajectory over the medium term. For now, these bigger structural questions have been punted to another day.

Parties may very well have missed a window to initiate these difficult discussions. Renowned economist Alberto Alesina has provided extensive cross-country analysis that demonstrates growth-friendly fiscal consolidation is a real thing (but only works when enacted in a counter-cyclical fashion to the economic cycle and is largely expenditure-based). Importantly, the window is usually within the first half of a government’s mandate. At the two-year mark of the next government, the Canadian economy should be well-past this downturn, and, keep in mind, it would likely take two years to execute any sort of broad-based expenditure review. With six recessions in Canada in the last 60 years, it is not inconceivable the economy faces another recession before it sees a balanced budget under plans proposed in this election.

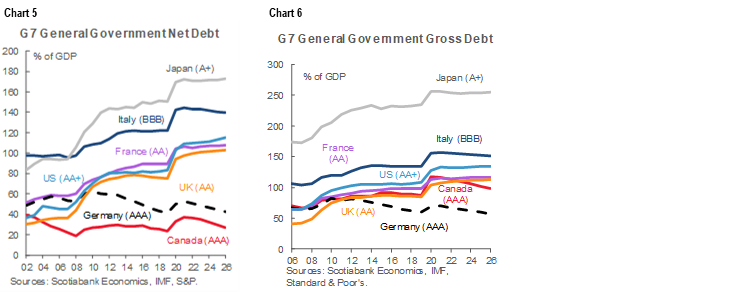

Nevertheless, Canada can still boast it is among the best (or at least less worse) of its peers. While the federal government has markedly increased its debt over the past 18 months, so too did all other major economies. The IMF projects Canada’s general government net debt (i.e., federal plus subnational debt after netting out assets) to be the lowest among G7 countries at around 37% in 2021, while its general government gross debt would be middle-of-the-pack (charts 5 & 6). Layering on platform commitments would not substantially change this picture. Liquidity differences between net and gross debt should arguably matter less at the present juncture given peak-crisis is behind us (and markets may well want to start considering outstanding pension obligations in long-run considerations). This is not a defense of profligate spending, rather a less-than-perfect benchmark when assessing potential funding risks in global markets where relativity matters.

Over the medium term, the fiscal path of other countries will (or should) matter to Canada. Markets could start differentiating across sovereigns should other countries start embarking on credible, growth-friendly consolidation paths over the next year or two. The UK and Switzerland, for example, have already started floating post-pandemic consolidation plans. Market observers may also become more discerning on other fiscal metrics like Canada’s persistent current account deficits, alongside its fiscal ones, as a broad indicator of weakening global competitiveness. Its weaker national savings could also point to an orientation towards consumption over investment at the expense of productivity and growth potential over the medium term.

Rating agencies have, for the most part, demonstrated tolerance for higher, temporary spending during COVID-19 across higher-rated sovereigns. Three of the four major rating agencies have recently reaffirmed Canada’s top tier borrowing status, with Fitch exceptionally downgrading Canada at the onset of the pandemic—with no material market impact. Canada still ranks highly on its strong institutional and policy fundamentals. This is unlikely to change under a range of likely election outcomes, but rating agencies will no doubt be looking for signs of permanent spending increases that do little to enhance growth. They will also be monitoring the impact on provincial finances, since in a practical sense, Canadian federal debt is only sustainable if provinces are sustainable given the implicit backing.

NOTHING TO SEE HERE

Global developments have been driving sovereign bond markets—Canada’s included—for some time. Rock-bottom policy rates and continued central bank purchases, along with bullish equity markets, have faded (or at least distorted) some relative attractiveness of bonds. But in a search-for-yield environment, Canadian spreads have remained tight, offering still-positive yields in a market where about USD17 tn in sovereign bonds are trading negative.

Election results will be digested in a complex global environment. US policy has—and has the potential to further—grabbed bond traders’ attention with its debt ceiling debacle continuing to play out as Canadian elections unfold, not to mention the potential for further massive fiscal packages south of the border. Markets will also try to interpret implications for central bank tightening. More fiscal support would underscore already-held views that the Bank of Canada will likely raise its policy rate ahead of the US Federal Reserve.

So far, election promises have not fazed markets, though they rarely price-in policy changes until they are firm. History discerns little difference across parties on post-election impacts on market metrics such as yields and currency movements in the immediate aftermath. Thus, any election impact is likely less about fiscal (or ideological) implications, rather more around the potential uncertainty on governance issues, namely how long before there is clarity on which party(ies) will ultimately form the next government and for how long.

SEPTEMBER 21ST

Political pundits may have plenty to chew on in the coming weeks (and potentially months), but markets will likely sit on the sidelines until the dust settles. Fiscal activism is likely already anticipated by markets. A minority government context introduces a degree of fiscal uncertainty—that will increase the longer it takes to establish a credible governance path forward—which could have markets guardedly positioned toward the election outcome itself. It could take a while for the fuller effects to be priced, and implications will likely only be known once a government is formed and a budget is tabled.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.