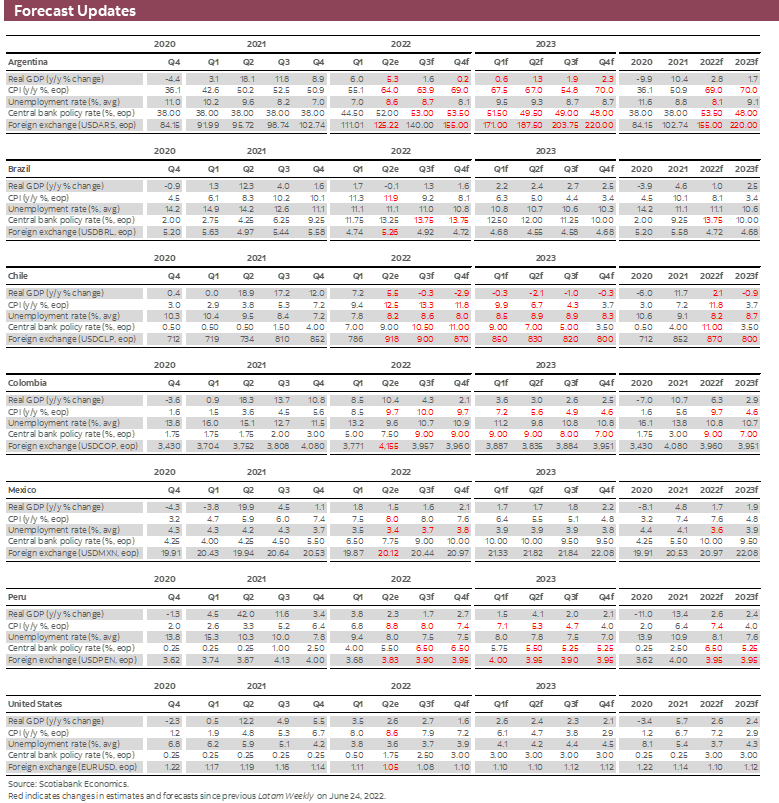

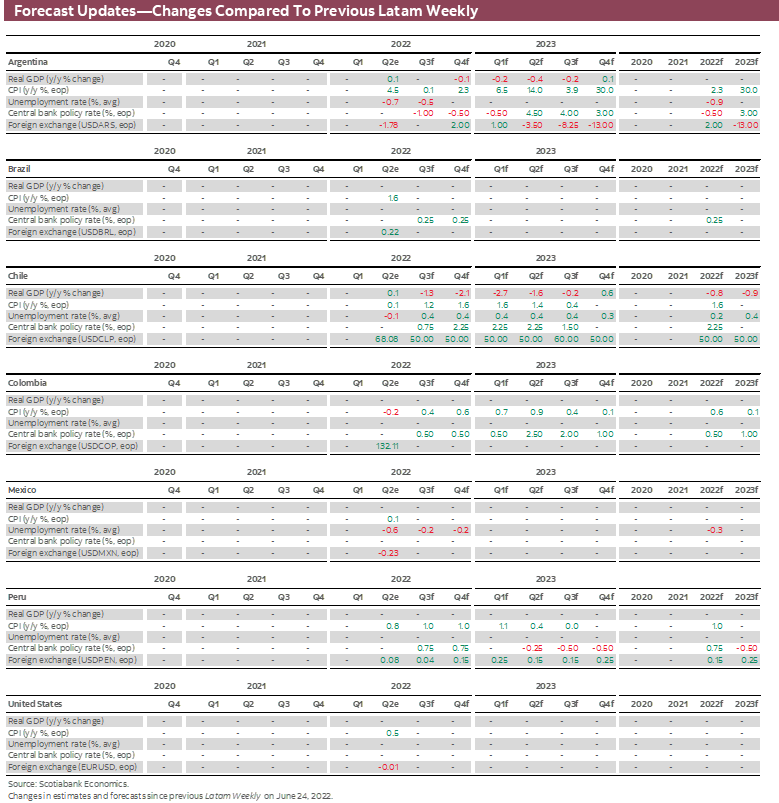

FORECAST UPDATES

- Continuing high inflation and aggressive monetary policy responses to it have led Scotiabank economists in the Latam region to revise their forecasts. See the latest changes to their projections in the forecast table below.

ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

- Persistently high inflation across the globe and the aggressive monetary policy responses to those price pressures have increased the risks of global recession.

- For the Latam region, higher US interest rates have fueled a strengthening of the US dollar in recent weeks that has led to rising concerns of exchange rate pass-through price pressures. Local currency depreciation adds to the policy challenges of calibrating tightening monetary conditions.

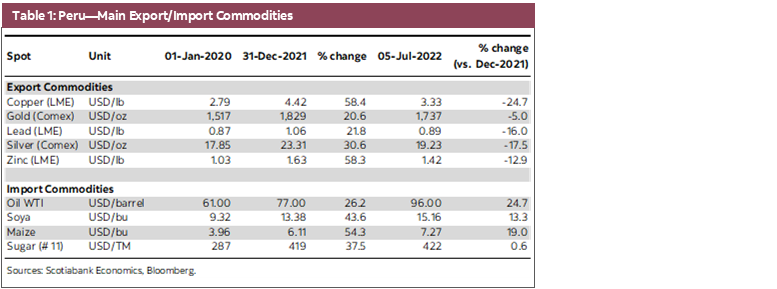

- At the same time, rising risks of global recession have led to a softening in commodity prices. While this development should relieve some pressures on inflation, both in the region and around the world, and thus interest rates, softer commodity prices could also have adverse terms of trade effects. Such effects would arise, for example, if prices of commodity imports (e.g., foodstuffs) remain elevated while commodity exports (e.g., base metals) decline.

- Despite the growing risks to the global outlook, the transition from recovery to expansion in most of the Latam region appears on track.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

- We assess key insights from the last week, with highlights on the main issues to watch over the coming fortnight in the Pacific Alliance countries: Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru.

MARKET EVENTS & INDICATORS

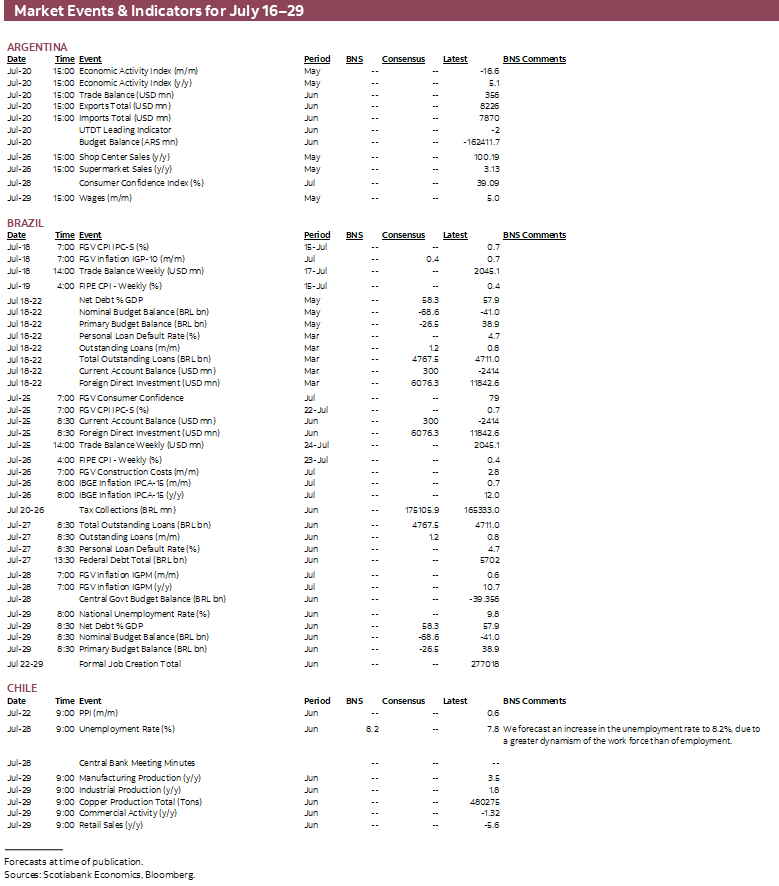

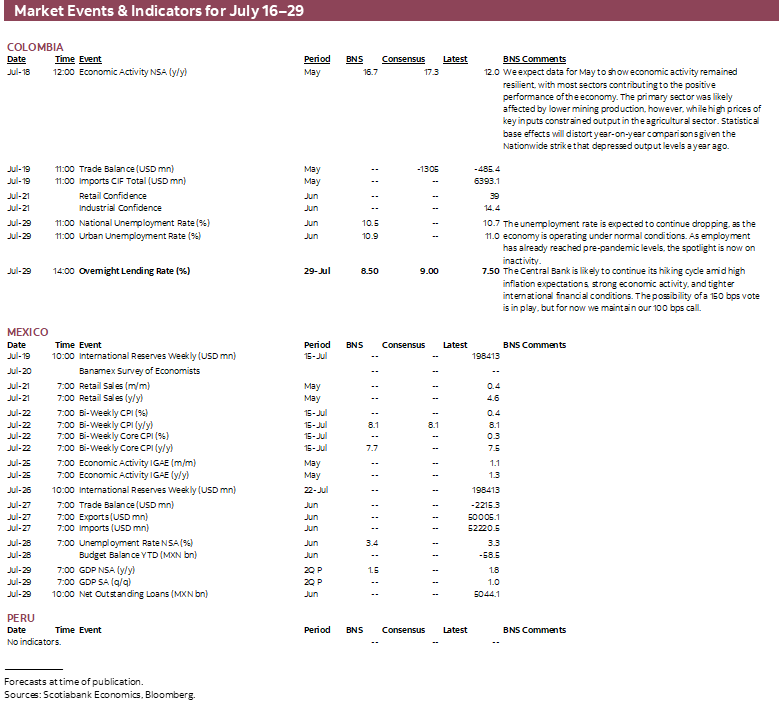

- A comprehensive risk calendar with selected highlights for the period July 16–29 across the Pacific Alliance countries, plus their regional neighbours Argentina and Brazil.

Economic Overview: The Fear of All Our Sums

James Haley, Special Advisor

416.607.0058

Scotiabank Economics

jim.haley@scotiabank.com

- The risk of global recession is on the rise. High inflation has led central banks around the world to both accelerate and amplify their policy tightening. With interest rates moving steeply higher, there is no shortage of potential shocks to global growth, including from overextended and mismatched public and private sector balance sheets.

- For the Latam region, recent increases in US interest rates and the prospect of further rate hikes to come, which have fueled a marked appreciation of the US dollar, add a further complication to the challenge of calibrating policy: domestic price pressures through exchange rate pass-through effects.

- Meanwhile, as global recession risks rise, commodity prices have softened. This could provide some relief from inflation, but may entail adverse terms-of-trade effects if commodity import prices remain high, for example, while prices of commodity exports fall.

- And while the need for central banks to contain price pressures and return inflation to target is not in dispute, it is possible that each central bank, operating in the context of a risk management framework, errs on the side of restraint. The result could be a cumulative response that entails excessively tight global financial conditions, giving rise to a fear of all our sums.

GLOBAL RECESSION RISK ON THE RISE

The global outlook has deteriorated in recent weeks, increasing uncertainty and the policy challenges facing the Latam region. The proximate cause of this deterioration, of course, is the persistence of high inflation around the world that is forcing inflation-targeting central banks to both accelerate and amplify policy tightening. And as interest rates move higher, faster, the risk of global recession increases. Acknowledging the risks to the outlook, the IMF recently announced that it would be revising down its forecast of global growth after it had already pared 0.6 ppts off its estimate for US growth this year. Coming on top of an earlier mark-down in April following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the Fund's latest projection will be closely watched.

There is no shortage of potential shocks to global growth. High levels of indebtedness among sovereign, non-financial businesses, and households are one source. Debt levels trended higher over the past decade, with the pandemic contributing to a step-jump in public and corporate debt loads (extraordinary policy responses supported households in many countries, limiting the deterioration in households’ balance sheets). Significantly higher interest rates that raise sovereigns' borrowing costs could thus lead to debt-servicing problems and expenditure cuts, higher taxes, and lower investment. While necessary, such policy responses would weigh negatively on short-term growth. Possible sovereign debt defaults by the most-highly-indebted countries would introduce additional uncertainties and further reduce investor risk appetite across multiple asset classes. Businesses with highly-leveraged balance sheets and households with exposure to potentially overvalued real estate assets are likewise vulnerable to interest rate shocks.

Balance sheet currency mismatches at the corporate level are another source of risk. Firms that borrowed in US dollars to exploit historically-low interest rates over the past decade, but which have revenues denominated in domestic currency, could experience debt-servicing challenges given the steep appreciation of the US dollar in recent weeks. The latest US inflation numbers could exacerbate this risk if, as Scotiabank's Derek Holt expects US CPI Tees Up Another Large Fed Hike, July 13, they lead to another big rate hike by the Fed later this month that fuels further dollar appreciation.

For the Latam region, the dollar's recent strength has already added to the policy challenges. There are several issues at play. To begin, domestic currency depreciation has added to headline inflation through exchange rate pass-through effects. Central bankers must be wary of such effects in calibrating their policy responses. And as our team in Santiago presciently predicted Latam Daily, July 7, the Chilean authorities have intervened in the foreign exchange market to slow the peso's depreciation. While the situation is especially pressing in Chile, given the currency's underperformance relative to other emerging market currencies, similar pressures are faced elsewhere.

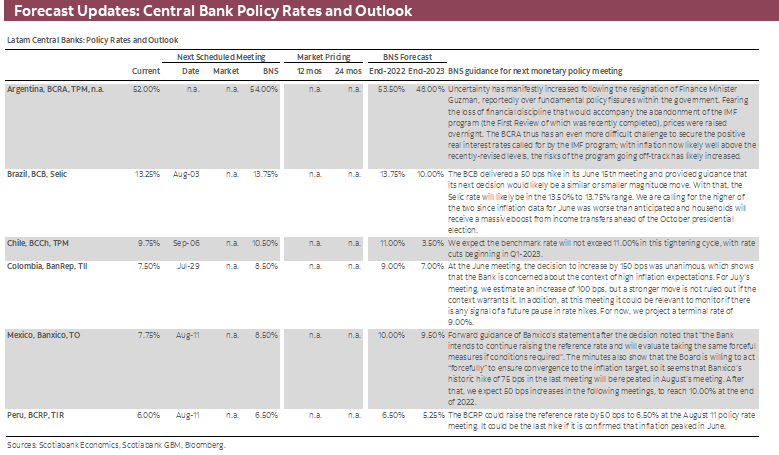

Such measures may provide a temporary respite from the effects of dollar appreciation, but they are unlikely to provide lasting relief. In this regard, policy rates may have to be raised still higher to contain inflation, posing a possible threat to domestic demand and growth prospects. Recent rate hikes by Latam central banks, including the 150 bps increase by Colombia's BanRep Latam Flash, June 30, and signals sent by Mexico's Banxico Latam Flash, July 7 teeing up another 75 bps rate rise in August, underscore the challenges.

At the same time, domestic currency depreciation that leads to higher prices for key imports—particularly foodstuffs—erodes households' purchasing power with damaging distributional effects. Efforts have therefore been made to shield lower income households from these effects with targeted fiscal transfers. Further efforts along these lines can be expected going forward.

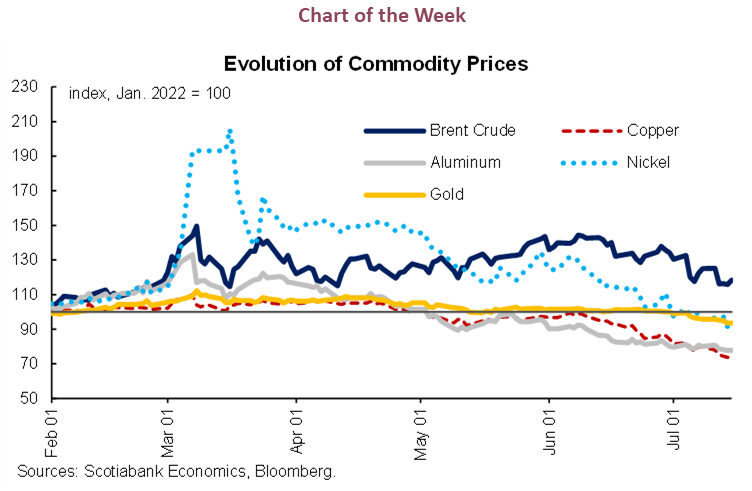

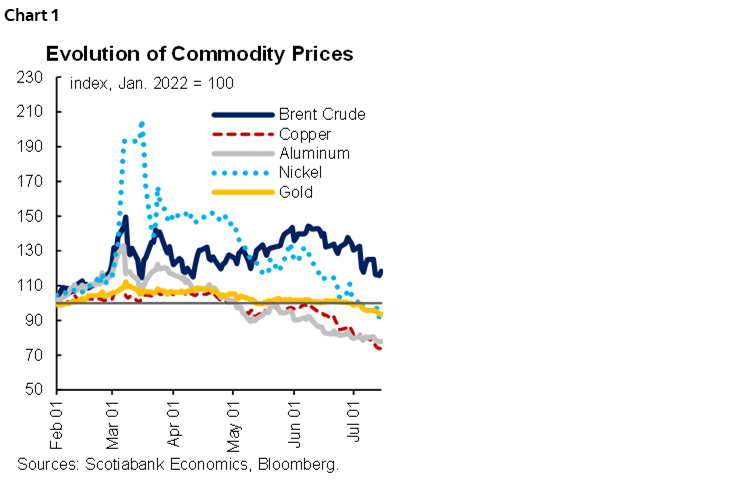

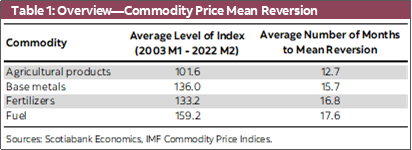

Rising risks of global recession, meanwhile, have resulted in a cooling of some commodity prices (chart 1). While this effect has the unambiguously beneficial impact of relieving price pressures, which could allow a somewhat lower interest rate path, it might also have unwanted terms of trade effects on Latam countries should commodity export prices (e.g., copper) soften as prices of commodity imports (e.g., foodstuffs) remain high (see the discussion on Peru in the Country Updates, below). As argued in previous editions of the Latam Weekly, commodity price spikes can be relatively ephemeral, with mean reversion exerting an important influence, and prudent policymakers are wise not to assume that higher prices will prevail over long planning horizons. In fact, back-of-the-envelope estimates based on IMF commodity price indices show that the average duration of episodes with prices above their longer-term averages range from about a year to a year and a half (table 1).

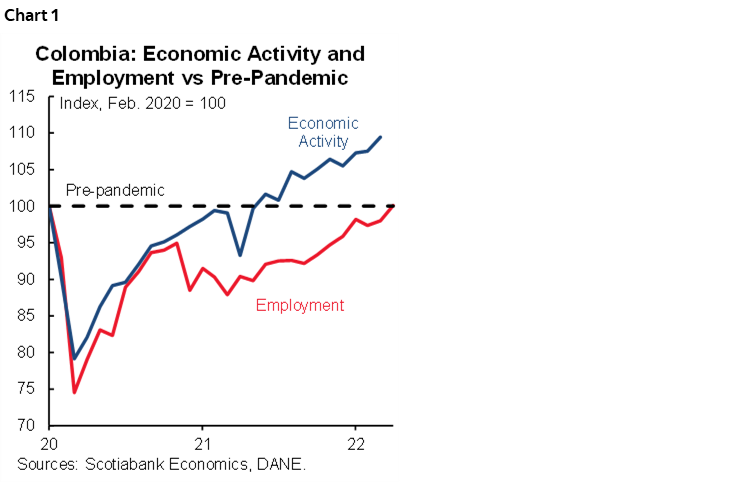

Yet, despite these challenges, grounds for cautious optimism remain. Growth in the Latam region remains buoyant and the transition from recovery to expansion seems on track. In Chile, for example, the monthly GDP reading in May provided an upside surprise to the BCCh's baseline scenario Latam Daily, July 4, while the Ministry of Finance revised up its projection for 2022 GDP growth Latam Daily, July 13. Similarly, consumer confidence has rebounded in Colombia Latam Daily, July 12, driven by good employment numbers, which should support strong consumption growth going forward. Moreover, governments across the region have reiterated commitments to medium-term fiscal sustainability, with strong rebounds in economic activity contributing to better-than-expected progress in reducing fiscal deficits.

Adherence to fiscal policy targets, coupled with fidelity to price stability commitments on the part of inflation-targeting central banks, guard against the risk of macroeconomic instability.

There is, however, one risk in the current conjuncture over which individual countries have little control. This is the possibility that the major central banks, conscious of criticism that they fell "behind the curve" in terms of miscalculating the persistence of inflationary pressures—or, through no fault of their own, failing to anticipate the serial nature of supply-side shocks—opt to err on the side of restraint in order to rebuild credibility. If each central bank independently makes such a determination, without considering the possibility that other central banks are likewise doing the same, the accumulated effect may be excessively restrictive monetary tightening and global financial conditions that increase the likelihood of recession.

And while it is possible that potential miscalibration from these responses could be assuaged by effective coordination among central banks, because each central bank has an individual incentive to demonstrate its inflation-fighting credentials, such coordination may be unlikely. It is this adding up of policy responses that gives rise to a fear of all our sums. It is why global recession risks are on the rise.

PACIFIC ALLIANCE COUNTRY UPDATES

Chile—Withdrawal of Monetary Stimulus Continues, Amid High Inflation and GDP Slowdown

Jorge Selaive, Head Economist, Chile

+56.2.2619.5435 (Chile)

jorge.selaive@scotiabank.cl

Anibal Alarcón, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl

Waldo Riveras, Senior Economist

+56.2.2619.5465 (Chile)

waldo.riveras@scotiabank.cl

COVID-19 SITUATION IN CHILE

The daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has continued to increase in recent days. The test positivity rate rose to 15%. For now, however, occupancy rates of ICU beds and COVID-19-related death rates are stable at low levels. Meanwhile, the vaccination campaign has reached 92.8% of the eligible population. The rollout of booster (third) doses continues—reaching 15.2 million people—and the new booster dose (fourth) is in progress—with 9.9 million people covered.

SLOWDOWN IN ECONOMIC ACTIVITY, AMID HIGH INFLATION FIGURES

On Friday, July 1, the central bank (BCCh) released GDP data for May, which expanded 6.4% y/y but fell 0.1% m/m. Commerce slowed as expected (-2.3% m/m), and industry fell again for the second month (-1.5% m/m), while construction staged a strong recovery (+1.4% m/m). Services remained resilient, though decreasing 0.1% m/m. Despite the slowdown in economic activity, the GDP figures positively surprised the expectations of both the central bank and the government. However, the very contractionary reference rate, the increased risk of a global recession trifecta (US, EU and China), and the non-market-friendly draft constitution could accentuate the slowdown during the second half of the year, but more markedly during 2023. At Scotiabank Economics, we expect GDP to expand 2.1% in 2022 and decline 0.9% in 2023.

While the labour market has begun to show signs of weakness, the unemployment rate remains below 8%. On Wednesday, June 29, the statistical agency (INE) released the unemployment rate for the quarter ended in May, which rose to 7.8%, a positive surprise given the somewhat higher market consensus (8.1%). For now, self-employment is offsetting the loss of salaried employment (public and private), symptomatic of the weakness of the labor market. However, its buffering role is not assured going forward, and labour market performance will largely depend on the ability of services to sustain employment, mainly those that are still somewhat lagging.

June's CPI number surprised on the downside, but the depreciation of the CLP will put pressure on inflation in the coming months. On Friday, July 8, the INE published the CPI for June, which rose 0.93% monthly (12.5% y/y), below the consensus (1.1%), but close to Scotiabank's projection of 1.0%. By components, the increase in June was largely explained by the contribution of volatile items. In our view, year-over-year inflation will only peak in August, when it is likely to reach 14%, with the result to be released just a few days after the referendum to approve or reject the new constitution.

GOVERNMENT PRESENTED THE TAX REFORM AND FISCAL SUPPORT MEASURES TO HOUSEHOLDS

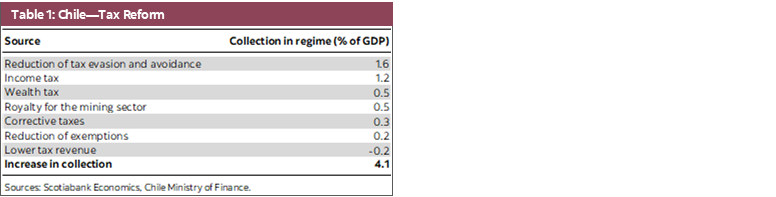

On Friday, July 1, the government presented its tax reform bill, which is intended to collect 4.1% of GDP to finance President Boric's social agenda (table 1). With this initiative, the government will introduce changes to the income tax, simplifying the tax system by separating company taxation from that of its shareholders. Likewise, the bill proposes measures to reduce avoidance and evasion, while eliminating some tax exemptions; reforms will also introduce modifications to the current Royalty bill for the mining sector.

Later, on July 11, the government announced fiscal measures to support households in the face of recent high inflation. The package proposes a fiscal transfer of CLP 120,000 (USD 120) to low-income families that will benefit around 7.5 mn people. Among other measures, the government will extend the Labor Emergency Family Income (IFE laboral) up to the Q4-2022 to encourage formal job creation. The fiscal cost of this package will reach USD 1.2 bn (0.4% of GDP) and will be financed from extra resources from income taxes, which will allow the fulfillment of the fiscal goals.

On Tuesday, July 12, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) published its Public Finance quarterly report, corresponding to the second quarter of 2022. A key change from the last report is the upward revision in GDP growth for 2022, which increased from 1.5% in April to 1.6%. The MoF also projects an improvement in the effective fiscal deficit from 1.7% to 0.1% of GDP for 2022, thanks to higher revenues than projected for income taxes, higher inflation, and the depreciation of the Chilean peso (CLP).

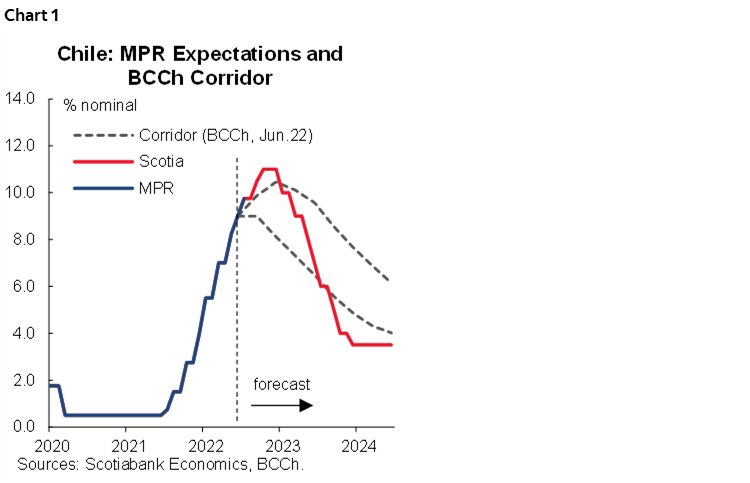

CENTRAL BANK RAISES THE POLICY RATE 75 BPS TO 9.75%

On Wednesday, July 13, the Central Bank (BCCh) hiked the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) 75 basis points, to 9.75% (chart 1), in a move that may have been intended to get ahead of market expectations. It is noteworthy that the reference to the future increases being of “lesser magnitude” was eliminated, which reflects the complex inflationary scenario that has determined the recent depreciation of the CLP. In our view, the MPR is likely to continue to rise to between 10.75% and 11% in October's meeting. Rate declines could start towards the beginning of 2023, conditional on a stabilization of the CLP and inflation, with the MPR around 3.5% towards the end of next year in this scenario.

A LOOK AHEAD

In the next fortnight, the central bank will release the minute of the July’s monetary policy meeting, on July 28. For its part, the statistical agency (INE) will publish the unemployment rate for the quarter ending in June to be released on July 28 and the economic activity by sector (on July 29).

Colombia—Balance of the First Half of the Year and What to Expect Ahead

Sergio Olarte, Head Economist, Colombia

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9166 (Colombia)

sergio.olarte@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Maria Mejía, Economist

+57.1.745.6300 (Colombia)

maria1.mejia@scotiabankcolpatria.com

Jackeline Piraján, Senior Economist

+57.1.745.6300 Ext. 9400 (Colombia)

jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolpatria.com

2022 could be defined as a year of transition. The world is experiencing a whole new scenario in which financial conditions are tightening, and uncertainty is high as markets balance recession risks. Given this context, Colombian assets have reflected international volatility, as well as high uncertainty coming from the presidential elections. Despite this volatility, however, Colombia’s economic performance has been favorable owing to domestic demand that has been stronger than expected. On the negative side, inflation has spiked to higher-than-expected levels, which has led the central bank to aggressively increase interest rates, joining in the worldwide tightening of monetary conditions. Looking ahead to the second half of the year, it will be important to follow the first steps of the new government, especially discussions about fiscal reform, which will only become louder, in the context of still-volatile financial markets.

In macroeconomic terms, the first half of the year has, on balance, been positive. The Colombian economy has expanded 9.3% y/y to April, still very strong, led by private consumption mirrored in a good performance in services-related sectors. The total reopening initiated in June 2021 hasn’t reversed; instead, by the end of June, the health emergency was declared over, and the economy is now operating under complete normality. This has led to a stronger recovery in employment, which had already reached pre-pandemic levels (chart 1). Moreover, consumer credit is expanding above 20% y/y and consumers have shown strong tolerance to the inflationary environment.

Ahead of the second half of the year, these trends appear robust, though our current GDP growth projection assumes a moderation in private consumption and a still-timid recovery on the investment side. That said, in H2-2021 we expect an expansion of 3.2%, which will result in growth of around 6.3% for the year. In this context, it will be important to monitor announcements from the new government that affirm (or contest) the view of more robust investment in the future. Ahead of 2023, we expect an expansion of 2.9%, which would be compatible with GDP’s long-term trend.

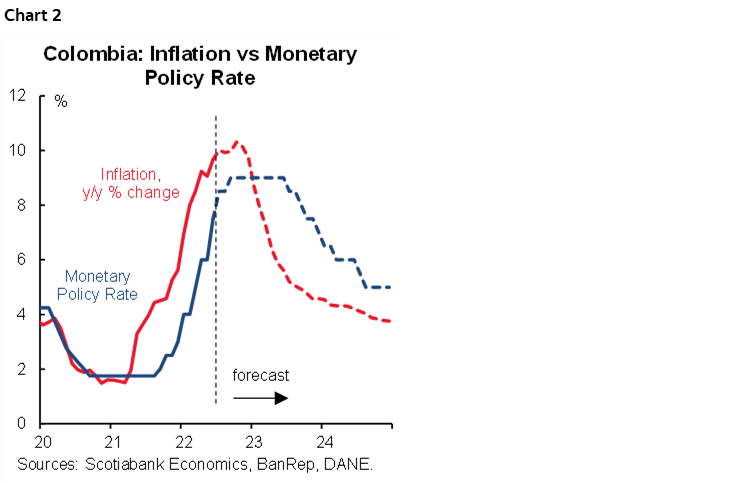

Inflation remains an issue, with headline inflation at a 22-year high and the balance of risks tilted to the upside. Inflation not only reflects supply pressures but also strong demand. Goods-related inflation has increased from 3.31% at end-2021 to 8.30% in June 2022, while services-related inflation has increased from 2.18% to 5.21%. A combination of indexation effects and strong demand is acting on prices. By the end of 2022, inflation is expected to reach 9.74%, with a moderation towards 4.6% in 2023, still above BanRep’s target range, as the base case. Upside risks will prevail, however, as gasoline prices are expected to continue increasing and supply shock also would continue counting in prices.

At the same time, resilient growth and increasing inflation that threatens to un-anchor expectations has led the central bank to ramp up its hiking cycle, raising the policy rate to 7.5% (chart 2). Going forward, we think that the central bank will continue increasing the policy rate to 9%, a high level compared with recent history, which is expected to last longer than usual (around one year). In 2023, rate cuts are expected to reduce the rate to 7%, which is still well above a level considered neutral (5%), but which would be consistent with a still high inflation environment.

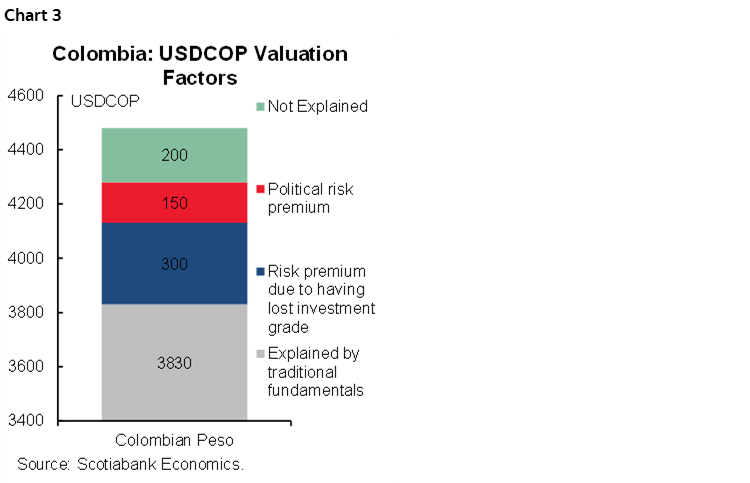

In terms of asset markets, interest rates and the FX have fluctuated widely. Fixed income rates are mainly guided by central banks' actions, while FX markets are pricing in a risk-off mode increased risk mood in international markets. According to a macroeconomic approach, the recent depreciation in the FX reflects international factors, especially fears about a potential worldwide recession. However, part of the recent movement is unexplained by macro factors. Our model suggests that the current risk aversion scenario is compatible with a 4300 pesos level; for now, trades above that level do not have a fundamental explanation (chart 3). That said, because we expect local assets to be guided by international volatility through the second half of the year, knowing where the Fed will end its’ hiking cycle will be crucial. Regardless, we expect volatility to remain.

On the political front, the new government is signalling that it will respect the independence of key institutions. For now, the cabinet is considered market positive and the President-elect’s intention to form a consensus suggests that the status quo in political decision-making process will prevail. In the same vein, vigilance of the first government’s steps is key, with fiscal reforms the next big topic.

Mexico—Not Too Good, But Not Too Bad

Luisa Valle, Deputy Head Economist

+52.55.5123.1725 (Mexico)

lvallef@scotiabank.com.mx

Last week, S&P and Moody’s updated Mexico’s sovereign debt rating and outlook. And even though both grades ended up on a similar level (S&P left the rating unchanged at BBB, while Moody’s downgraded it to Baa2) and both outlooks were upgraded from negative to stable, the messages are very different.

S&P’s outlook upgrade arises from Mexico’s prudent fiscal and macroeconomic policies through uncertain times. Also, while recognizing Pemex and CFE complexities (and the almost certainty that the government will support these companies, if necessary) S&P expects that the current administration will keep its finances under control (even if they need to support Pemex) while balancing the fiscal pressure arising from gasoline subsidies in a low growth/high inflation and high interest rates environment.

Now, if this story sounds almost “too good to be true”, in our view, Moody’s assessment reflects a more realistic assessment of economic landscape. Moody’s downgrade highlights, along with S&P, the “prudent macroeconomic management” that has helped Mexico maintain its debt metrics so far. However, Moody’s acknowledges more structural challenges that will continue to undermine the economic recovery, even in the medium term. To start with, private investment has been the weakest link in Mexican economy since the airport cancellation in 2018 and it will continue to face regulatory uncertainty that harms the prospects of nearshoring, even under the UMSCA framework. Additionally, despite limited government expenditure in response to the pandemic, subsidies, pension expenditures, flagship projects, and Pemex (which was also downgraded to B1 from Baa3 and whose debt obligations add up to more than $20 billion through 2024) will add pressure to fiscal accounts.

What now? We think that the reality is between these two stories. In the short term, we anticipate a bounce in investment in Mexico due to some nearshoring, specially linked to manufacturing projects and in line with rising production costs in the US. Will Mexico grow more than 2% in the next two years? Let’s hope so, but it is unlikely. We think that Mexico’s GDP will grow 1.7% this year and 1.9% in 2023. Will Mexico’s credit metrics keep deteriorating? Probably, but not to the point where Mexico loses its investment grade. So, going forward, the story is much of the same we have seen so far, not too good but also not too bad.

Peru—As a Harrowing Year Ends, What Will the New Year Bring?

Guillermo Arbe, Head Economist, Peru

+51.1.211.6052 (Peru)

guillermo.arbe@scotiabank.com.pe

At the end of July President Castillo will have completed his first year in office. And what a year it has been! At this time last year, fears abounded—fears of a regime that was clearly anti-business and which could conceivably seek the expropriation of gas and mining operations, or call for a Constitutional Assembly.

In the end, this worst-case scenario of a radical government with a clear leftist agenda has not materialized. What has occurred, however, has been far from reassuring. The Castillo government is not the leftist juggernaut once feared, but is rather an administration with no clear agenda; one lacking expertise in state management, and besieged by corruption scandals. It is permissive towards violent social conflicts and in constant conflict with Congress, the press, the judicial system and, more recently, with the army and police forces.

Perhaps the most worrisome risk extant is the weakening of the rule of law. The government is extremely permissive regarding the informal/illegal economy, which is expanding, on occasion even encroaching on formal operations, as evidenced when informal miners invaded property of formal copper mines over the last few months.

And, yet, not all is wrong. True, state institutions have weakened through questionable appointments, but it is also true that there has been a healthy reaction by institutions and society. The press has exposed cases of government malfeasance and ineptitude. Congress has confronted or removed many of the more unsatisfactory government officials. And the Attorney General's office is investigating questionable actions and persecuting members of the government.

Moreover, Peru’s economy has experienced mild to moderate GDP growth. Three factors have sustained this growth. First, a huge amount of resources have been pumped into the hands of consumers through pension fund withdrawals, access to worker compensation funds, and government transfers. Second, and perhaps the single most noteworthy decision of the Castillo government, economic institutions, including the Ministry of Finance, the BCRP, the superintendency of banks, and the tax administration, have all been kept in capable hands, within solid institutions. The third factor that has sustained growth has been a prolonged period of high metal prices, which, together with credible economic institutions and policy, have ensured strong macro balances.

Despite this favourable conjuncture, the first year of the Castillo regime has been so fraught with instability, uncertainty and surprises, that we are looking forward to what the second year might hold with bated breath. We hope to get a picture of what lies ahead from the President’s mandatory address to the nation on July 28. Changes in the cabinet, which typically (but not always) occur around this time, would be even more telling for the future of government performance. The latest cabinet changes, in May, improved the cabinet by replacing questionable ministers with more professional personnel at the ministries of Mining, Agriculture and the Interior. There is some talk that the head of the cabinet, Manuel Torres, may be replaced. If so, the name of his successor will be key in defining the orientation and capability of the government.

Another important change in July will preside over Congress. The level of fragmentation in Congress is such that negotiations for the new leadership are convoluted. Whoever is chosen to preside Congress will define its relationship with the Executive, as well as the agenda for the coming year, including the possibility of a new attempt at a presidential impeachment.

At the same time, the Castillo regime will face a very different economic environment in its second year. Metal prices have fallen (table 1), inflation is rampant and interest rates are rising quickly. Inflation is already affecting domestic purchasing power, and declining metal prices will impact fiscal and external accounts. However, lower purchasing power is being offset by a new round of pension fund withdrawals, and macro accounts are facing declining metal prices from a position of strength. This environment is manageable, as long as economic leadership, policy and institutions remain in the capable hands they are today. Accordingly, we do not see a need to modify our GDP forecast of 2.6% growth for 2022 and 2.4% for 2023.

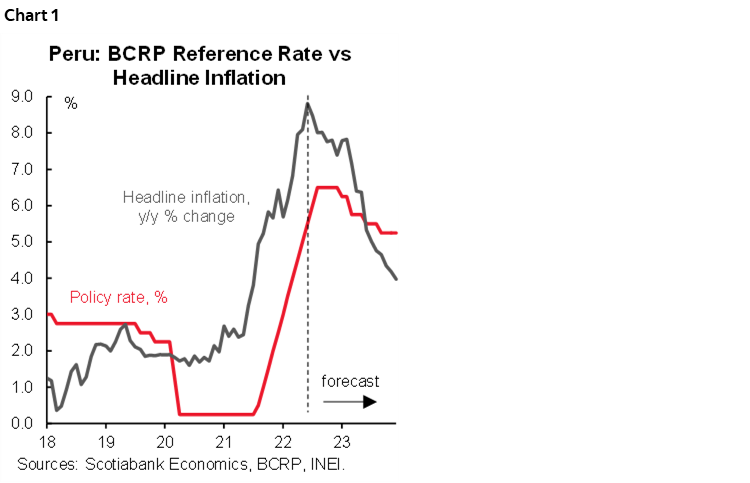

The BCRP raised its reference rate to 6.0% in early July, following a reading of 8.8% inflation in June (chart 1). The BCRP believes that inflation will peak in July. They may be right, as the turnaround in global commodity prices begins to filter through to local goods. However, the BCRP is likely to prefer prudence, and reinforce its anti-inflation message by one last increase in the reference rate to 6.50% in August. Inflation going forward seems likely to soften at a slower pace than we initially thought, and we have raised our year-end 2022 forecast to 7.5%, from 6.4%.

Meanwhile, the decline in metal prices has done damage in the FX market. In just a few weeks, the PEN shot up from a range of 3.65–3.70 to 3.90–4.00. We are raising our FX forecast for 2022 from 3.80 to 3.95. Signals are mixed for 2023, and markets are too volatile for conviction, but to expect the PEN to appreciate to 3.70 in 2023 now seems a bit audacious. We are raising our forecast, from 3.70, to 3.95 for year-end 2023.

As his second year begins, President Castillo has the opportunity to embark on a new path, as well as to improve the quality of the cabinet. If he does not do so, then the second year of his term could well be a repeat of the instability, uncertainty and frequent surprises that characterized his first. Let’s just hope he continues to leave economic institutions alone.

| LOCAL MARKET COVERAGE | |

| CHILE | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | anibal.alarcon@scotiabank.cl |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| COLOMBIA | |

| Website: | Forthcoming |

| Subscribe: | jackeline.pirajan@scotiabankcolptria.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish and English |

| MEXICO | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudeco@scotiacb.com.mx |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| PERU | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | siee@scotiabank.com.pe |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

| COSTA RICA | |

| Website: | Click here to be redirected |

| Subscribe: | estudios.economicos@scotiabank.com |

| Coverage: | Spanish |

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.