The federal government committed to making “a significant, long-term, sustained investment” in a national childcare system in Canada in its recent Speech from the Throne.

This is welcomed (and long-overdue), but if history is any guide, it could take years to bear tangible results—if the government, its priorities, or its political capital haven’t changed in the interim.

COVID-19 has dramatically strengthened the economic argument to promptly provide incentives to help women maintain or deepen their participation in the labour market.

- Parents are struggling to maintain their connection to the labour market as they juggle childrearing responsibilities with work demands. In September, 70% of mothers reported working less than half of their normal hours relative to September 2019.

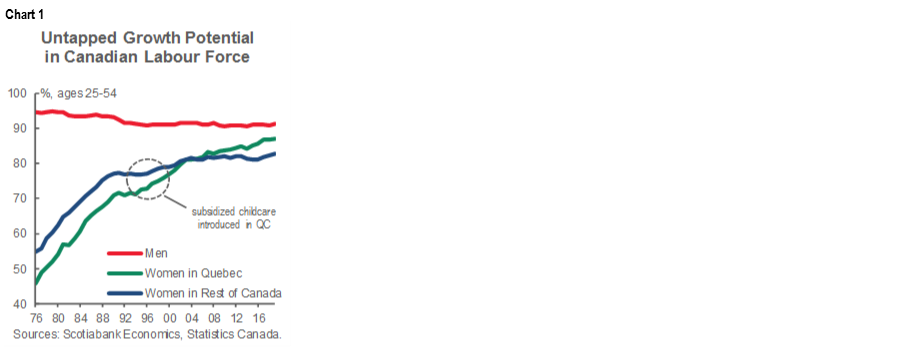

- As the pandemic wears on, this risks exacerbating disparities in labour force participation between men and women that pre-date the pandemic (chart 1).

Access to affordable and safe childcare is critical in this regard. We propose some immediate, market-driven steps that the government can take now to increase affordability of care, while increasing the number of spaces, as the government works on its long-term solution to childcare. These include:

* A substantial increase to household transfers linked explicitly to childcare expenses that could be delivered in a timely and efficient manner through the Canada Child Benefit program;

* A large increase in tax credits for early childhood education that could be delivered through the Canada Childcare Tax Credit; and

* A matching grant for home-based childcare settings to upgrade or create new childcare spaces.

If implemented, these measures would meaningfully help alleviate household affordability strains, lift labour force participation, and underpin Canada’s economic recovery.

While these would be costly—around $15 bn—they should provide some fiscal offsets through demand-creation and higher labour force participation, which should spur economic output and bolster government revenues.

SUBSTANTIAL COSTS BORNE BY FAMILIES

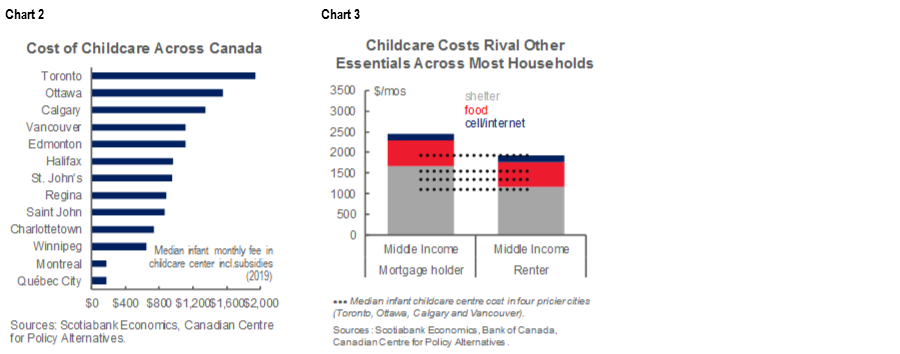

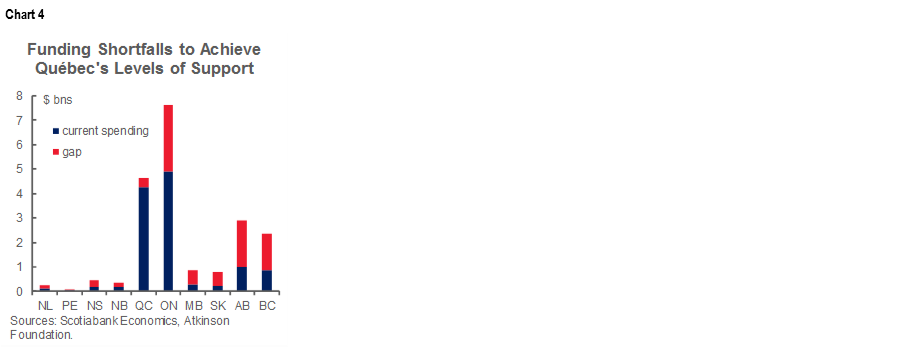

Childcare is likely the largest household expenditure for the average Canadian family with two (or more) children in full-time care. Market prices in Toronto, for example, can exceed $2 k per month per child, while other cities approach these numbers even after subsidization is factored in (chart 2). These prices exceed even shelter costs for the vast majority of Canadians (chart 3). Not surprisingly, less than 55% of Canadian children (≤5) outside of Québec attend a formal childcare program, far short of the 70% OECD average and even further below Québec’s attendance levels of almost 80%. For many families, childcare is even less affordable than housing and is an unattainable luxury.

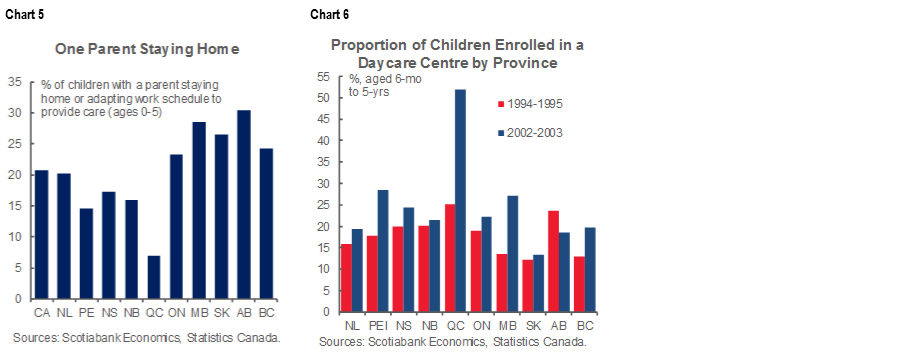

Childcare is chronically underfunded across most of the country. As this falls under provincial jurisdiction (and municipal in some instances), there is variability in funding across provinces, but the shortfalls are broad-based (with Québec an outlier). Preliminary figures according to the Atkinson Foundation suggest that an additional $8 bn on top of current provincial spending (estimated at $12 bn) would be required to lift Canadian-wide supports to Québec’s level of generosity (chart 4).

The Speech from the Throne in September promised a “significant, long-term, sustained investment” in childcare. This is a welcomed development but it will take sustained and substantial efforts—fiscal and otherwise—to bring about tangible results given complicated jurisdictional issues and the patchwork system that exists across the country. All of this will take time. An interim solution is required, one that cannot let perfection be the enemy of the good.

THE ECONOMIC CASE FOR MORE

There is an urgency to take immediate steps to support parents—and mothers in particular—in balancing competing demands of work and childcare. While women’s participation in the labour force returned to pre-pandemic levels in September with school re-openings, mothers worked far fewer hours. About 70% of mothers reported working less than half their usual hours relative to last September according to September’s Labour Force Survey. With precarious outlooks for schools at present, parents face uncertainty in the months ahead as they continue to confront the “impossible choices between kids and career”. Meanwhile, the Bank of Canada recently marked down its estimate for Canada’s potential growth to about 1 percent a year through 2023 owing to a variety of factors including lasting labour market impacts from the pandemic.

Preferences may very well have shifted as a result of the pandemic. In a June Statistics Canada survey, almost a third of parents of both preschool- and school-aged children indicated they did not plan to send their child to childcare as facilities reopened, with 88% citing health-related concerns. At the same time, more families are reportedly looking for alternatives. The Canadian Online Job Dashboard (that tracks Job Bank and Indeed sites among others) currently notes a surge in demand for “home childcare providers” of 17% y/y. Families in the near term at least may very well be looking for smaller, more flexible arrangements.

Canadian women were already measurably absent from the workforce relative to their male counterparts prior to the pandemic. The participation gap stood at almost 8 ppts (ages 25–54) last year. The International Monetary Fund has estimated that closing this gap could lift Canada’s GDP levels by 4% over the medium term (by $92 bn), reflecting not only greater supply, but also a productivity boost given higher educational attainment levels of Canadian women relative to men. In effect, closing this gap would lift Canada’s labour force by about half a million.

Affordable childcare is a substantial barrier to greater workforce participation for many women. The marginal benefit to working is simply overwhelmed by its cost in most jurisdictions across Canada with many women opting to stay at home (chart 5). Québec has bucked this trend with its introduction of a universal, low-fee childcare program in the mid-90s. Childcare attendance doubled in the aftermath, whereas improvements across the rest of the country were modest (chart 6). This gap persists today.

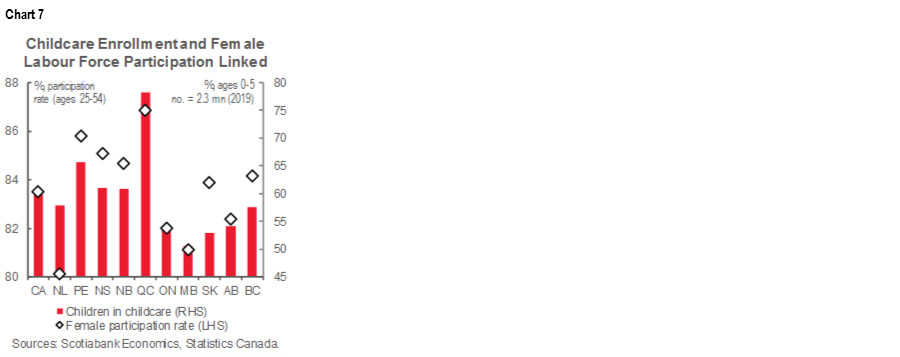

Importantly, Québec has also made substantial progress in narrowing its labour force participation gap, whereas the rest of the country has been relatively flat over the last two decades. There is a solid link between childcare enrollment and working-age labour force participation among females across Canada (chart 7).

A CLASSIC MARKET FAILURE

The under-provision of affordable and quality childcare is a classic market failure. Quality childcare is a public good with positive externalities—much like education—with broader welfare and economic benefits, but the costs are largely borne directly by Canadian households with children. With many families simply unable to afford the market-clearing price of decent options in Canada, there is a chronic shortage of supply. The system is reliant on the public provision of spaces. With stretched provincial budgets and public investment bottlenecks, too many families are chasing too few spots which puts further upward pressure on prices, while limiting choice and buyer bargaining power.

Most provinces and municipalities continue to rightly tackle supply constraints with targets for the provision of new spaces at subsidized prices. There is a need to double-down on these efforts, but this will take time. Caution is also warranted with using a fee-setting approach without sufficient supply and funding underpinning the targets as this can further compound the mismatch.

There is also no one-size-fits-all approach. Even the more established Québec model has highlighted a role for public and private options, as well as larger institutional settings and smaller home-based ones. When demand outstripped the provision of public spaces, the provincial government also introduced tax credits to allow families to pursue private options with about 35% of Montreal daycare spaces, for example, provided at market rates.

Market-led approaches that focus on demand can compliment and potentially accelerate supply-led efforts. In particular, directly supporting parents with affordability challenges so that more families can afford market-clearing prices is a reasonable approach, which in turn should spur a supply response by the private sector. Or at least bridge a gap until enough political pressure mounts for municipal or provincial authorities to create more spaces at higher prices if required.

The government role in providing regulatory frameworks and oversight is critical under both supply and demand approaches. This will have the biggest influence on quality, regardless of the delivery model.

SIMPLE STEPS ON THE ROAD TO LOFTY GOALS

A universal and affordable childcare system in Canada is an appropriately aspirational goal. But there are steps the government can take now that could yield immediate benefits—for household affordability, for Canada’s labour markets and its broader economy—while still being consistent with longer term objectives.

1. Putting money in pockets when and where it is needed now

There is a compelling case to provide a top-up in cash transfers to households struggling to balance work and childcare needs. There are a variety of ways this could be delivered, but a simple approach would be to top-up to the Canada Child Benefit (CCB), but instead of means-testing the amount, make it contingent on childcare enrollment. The CCB has made important strides in lifting more children out of poverty, with a pre-pandemic price tag exceeding $25 bn annually, but it has not had a measurable impact on improving female labour force participation. Nor was it designed to, but at this juncture, it could be leveraged to this end.

A top-up of $5 k per year (or about $400/mo) would bring support (on average) roughly in line with Québec’s subsidization. This would still fall short of actual childcare costs in Canada, but it would tilt the calculus of the marginal cost of workforce participation in the right direction: whether it is considering a return to work, a decision to stay in the workforce, or to work more hours. Over the medium term, if childcare enrollment were to attain Québec’s levels, this would mean an additional 400 k children (≤5) in a childcare arrangement bringing the total to 1.8 mn. This would imply annual costs of around $8 bn for such a top-up for children five and under. Applying this to school-age children (with another 2 mn children ≤12) could push the costs upward to $15 bn, but a case could be made to scale support for older ages given lower childcare costs. For illustrative costing purposes, a top-up for older children at half this rate would add another $5 bn to the cost for a total incremental cost of $12 bn.

2. Reflecting the wide variability in childcare costs (and benefits) across the country

The substantial variability in market prices, as well as provincial and municipal supports, for childcare across the country renders pan-Canadian policy design challenging. This would argue for complementing the CCB top-up with a tax credit that would offer additional benefits to those families facing higher costs well in excess of the proposed CCB offset, while receiving fewer provincial supports.

The Canada Childcare Tax Credit could be substantially expanded to reflect these differences. The CCTC currently allows parents to deduct up to $8 k a year per child under 7 from taxable income. Increasing the tax credit to $20 k a year should cover the cost of daycare in the most expensive cities (for example, in Toronto), and as a non-refundable tax credit, would only provide benefits against actual expenses. (Note, the existing tax infrastructure supporting CCTC claims also provides a check-and-balance against childcare enrollment claims under the proposed conditional CCB top-up.)

The fiscal cost of the CCTC under current limits runs around $1.5 bn per year. The benefit to individual families would vary widely, depending on actual expenditures, as well as household income, but with 1.4 mn children (≤5) in childcare (and more, but unquantified in pre/afterschool care), this provides an approximate average $1k/year benefit per child. For example, a 2-parent household earning a mean household income with two children in full-time care in Toronto at an annual expense of $42 k would see a benefit of about $9 k. The same family in Montreal, paying $4 k annually in childcare would receive about $1 k in tax relief. On the other end of the spectrum, a single parent on low income would receive little benefit as their effective tax rate would be close to zero. A 2.5 times increase in the deduction limit would likely result in an approximate doubling of the total cost of the program (It would not be a one-for-one increase as a significant number of claimants will already have relatively low marginal effective tax rates.)

3. Tapping market forces to help build supply

Major efforts on supply will be needed over the long run but these will take time to come on line. There are market-driven approaches to encourage supply in the near-term that would be consistent with a longer term expansion of publicly supported childcare spaces. One in five Canadian children (≤5) under a formal childcare arrangement is currently in a home-based setting, with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives data suggesting family-based fees tend to cost a quarter to a third less than centre-based ones.

A matching grant to encourage the upgrading of existing or creation of new home-based childcare arrangements could be introduced relatively quickly. A 50% matching grant of up to a maximum of $20 k could be applied against the costs of renovations, as well as childcare materials and equipment. Such a grant could help improve the quality of existing home-based arrangements, or spur the creation of new spaces, with upfront disbursements removing financing hurdles. It could also encourage the formalization of home-based childcare provision with the grant conditional on being registered with provincial authorities. It could be delivered at a relatively low cost in the order of $250 mn.

PAYING ECONOMIC DIVIDENDS

These proposals would also provide a near-term boost to demand at a time when the economy is operating under potential. Such measures combined could amount to around $15 bn, the bulk of which would flow through the CCB top-up. The fiscal multiplier of such a top-up should be relatively strong given the high propensity to spend among families, in general, and in this particular case, the explicit conditionality linked to expenditure (i.e., childcare enrollment). While some estimates put the multiplier as high as 2, a more conservative estimate of 0.75 would suggest a lift in output of about a third of a percentage point of GDP through direct consumption. The matching grant for renovations could also support near-term demand in both construction and retail segments with a similar multiplier, though the quantums are much smaller.

The combined measures should also support job growth. Over the medium term, bringing an additional 400 k children into formal childcare arrangements (i.e., on par with Québec’s levels) could support an additional 65–75 k positions assuming worker-child ratios of 1:5. The number could be even higher if some families opt for private arrangements. There would also be indirect job creation as increased net household incomes for families would drive stronger consumption.

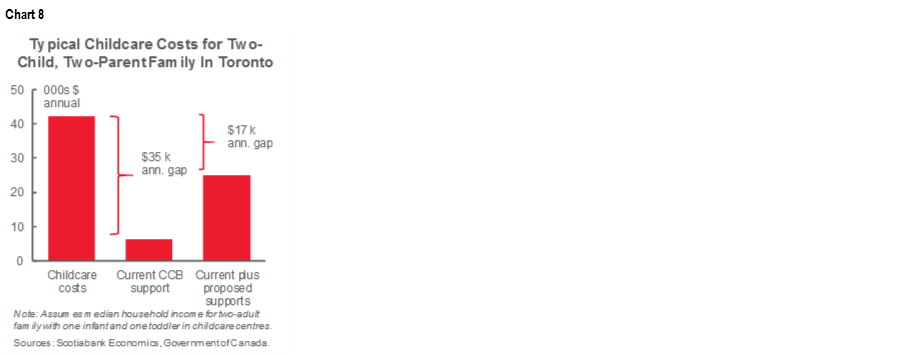

Such proposed measures could potentially halve the funding gap for households in some of Canada’s more expensive cities for childcare. For example, a two-parent family earning a mean household income with two children in full-time childcare centres in Toronto could reasonably be paying $42 k annually with only a modest offset from current CCB supports. Proposed measures could potentially halve the funding gap to about $17k per year for this family (chart 8). This is still a high cost, but it still would provide very substantial relief in high-consumption years for Canadian households. This is illustrative only and program design would need to adjust support levels, in particular, for single-parent households.

This should support stronger attachments to the labour force among Canadian women. An additional 400 k children under childcare arrangements could enable about 250 k parents otherwise responsible for childcare to enter or return to the workforce in some capacity. This is still shy of the half-million figure that would close the female-male gap completely and fuel the IMF’s 4% growth dividend, but it is a good start.

These full impacts would not transpire immediately but all of these proposed measures could be enacted relatively quickly with early and immediate benefits for households and for the economy. Amounts can also be scaled in both directions, but marginal amounts that still fall well-short of childcare costs are not likely to have pronounced effects on labour force participation (and longer term growth potential). Rather, the impact would mainly feed through consumption channels largely supporting near-term growth.

These combined measures still fall short of a universal, low-fee childcare program but they would provide rapid and meaningful financial support and incentives for parents to place their children in daycare, and for daycare operators to increase the number of available places.

DISCLAIMER

This report has been prepared by Scotiabank Economics as a resource for the clients of Scotiabank. Opinions, estimates and projections contained herein are our own as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. Neither Scotiabank nor any of its officers, directors, partners, employees or affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents.

These reports are provided to you for informational purposes only. This report is not, and is not constructed as, an offer to sell or solicitation of any offer to buy any financial instrument, nor shall this report be construed as an opinion as to whether you should enter into any swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. The information contained in this report is not intended to be, and does not constitute, a recommendation of a swap or trading strategy involving a swap within the meaning of U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission Regulation 23.434 and Appendix A thereto. This material is not intended to be individually tailored to your needs or characteristics and should not be viewed as a “call to action” or suggestion that you enter into a swap or trading strategy involving a swap or any other transaction. Scotiabank may engage in transactions in a manner inconsistent with the views discussed this report and may have positions, or be in the process of acquiring or disposing of positions, referred to in this report.

Scotiabank, its affiliates and any of their respective officers, directors and employees may from time to time take positions in currencies, act as managers, co-managers or underwriters of a public offering or act as principals or agents, deal in, own or act as market makers or advisors, brokers or commercial and/or investment bankers in relation to securities or related derivatives. As a result of these actions, Scotiabank may receive remuneration. All Scotiabank products and services are subject to the terms of applicable agreements and local regulations. Officers, directors and employees of Scotiabank and its affiliates may serve as directors of corporations.

Any securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. Scotiabank recommends that investors independently evaluate any issuer and security discussed in this report, and consult with any advisors they deem necessary prior to making any investment.

This report and all information, opinions and conclusions contained in it are protected by copyright. This information may not be reproduced without the prior express written consent of Scotiabank.

™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. Used under license, where applicable.

Scotiabank, together with “Global Banking and Markets”, is a marketing name for the global corporate and investment banking and capital markets businesses of The Bank of Nova Scotia and certain of its affiliates in the countries where they operate, including; Scotiabank Europe plc; Scotiabank (Ireland) Designated Activity Company; Scotiabank Inverlat S.A., Institución de Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V., Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, Scotia Inverlat Derivados S.A. de C.V. – all members of the Scotiabank group and authorized users of the Scotiabank mark. The Bank of Nova Scotia is incorporated in Canada with limited liability and is authorised and regulated by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. The Bank of Nova Scotia is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and is subject to regulation by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and limited regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority. Details about the extent of The Bank of Nova Scotia's regulation by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority are available from us on request. Scotiabank Europe plc is authorized by the UK Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the UK Prudential Regulation Authority.

Scotiabank Inverlat, S.A., Scotia Inverlat Casa de Bolsa, S.A. de C.V, Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat, and Scotia Inverlat Derivados, S.A. de C.V., are each authorized and regulated by the Mexican financial authorities.

Not all products and services are offered in all jurisdictions. Services described are available in jurisdictions where permitted by law.