We all want to spend less, save more and plan for the future. We don’t always do that, but why? In our Ask a Behavioural Economist series, we are talking to Dr. Raj Sandhu, a behavioural economist.

Behavioural Economics is the scientific study of decision-making that examines the psychology behind an economic outcome, basically why we do what we do with our money. If we can understand the reasons behind our spending and saving habits, we can set ourselves up to make better decisions for better outcomes.

We talk to Raj about common behaviours that get in people’s way and how we can work to overcome them. These sorts of behaviours are called behavioural biases.

For this edition, we are looking at extremeness aversion (aka Goldilocks effect). Raj breaks down how this affects us.

What is it?

It’s our tendency to pick the middle ground, or in other words, to avoid choosing the extreme options.

Give me an example of how this works.

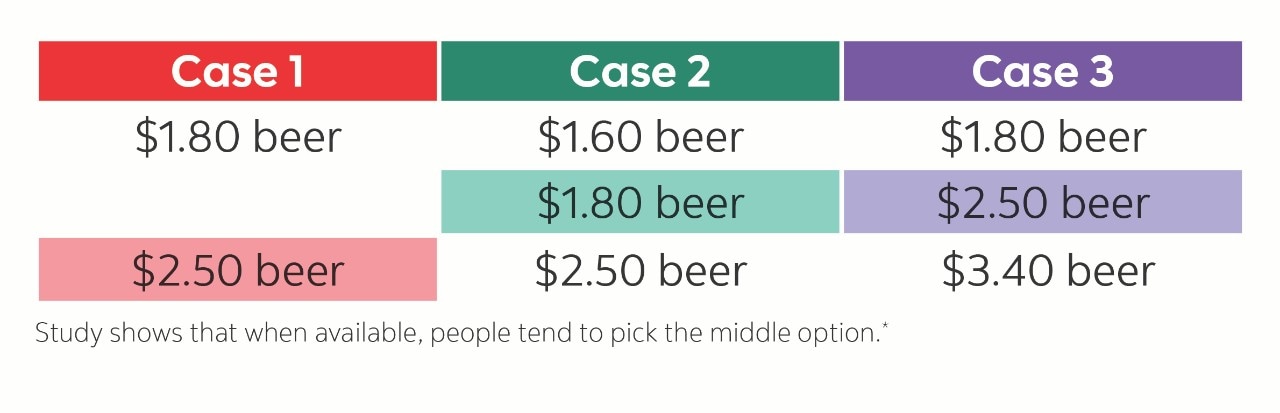

You are at a bar and can choose between a bottle of beer for $2.50 or the same sized bottle for $1.80. If you are like most people, you chose the more expensive beer. The next time you go to a bar, you are also offered a third lower-priced beer that’s $1.60. In this case, you are most likely to choose the $1.80 beer, the middle option. And if the $1.60 beer is replaced with a more expensive $3.40 beer, the favourite shifts again to the middle option.

What this all means is that we evaluate options in a relative, not an absolute way. Things are only cheap or expensive when they’re compared to something else – and when all else is equal, we typically don’t want the cheapest or the most expensive (an exception to this is the decoy effect which we will talk about in a future Ask a Behavioural Economist piece, which shows how people can be nudged towards the extreme option).

How does that affect me?

What this shows is that while we have our preferences, the decisions we make are really heavily influenced by the choices we have and how those choices are presented to us. A common example of this is when we are buying coffee, we tend to choose the middle size option rather than asking ourselves, how much coffee do I really want to drink?

How do I tackle that?

This can be hard to overcome, because it’s our brains way of simplifying our decision making process. But what you can do is to know what your needs are before you go shopping, and try to evaluate how each option meets your needs instead of comparing the options to each other. Think about what you really want and need before picking the default middle option.